|

|||||||||||||||||

November 2009 Web Edition Issue #3 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mondo Cult Forum Blog News Mondo Girl Letters Photo Galleries Archives Back Issues Books Contact Us Features Film Index Interviews Legal Links Music Staff |

They Spit On His GraveRemembering the Hollywood Memorial

by Michael Copner

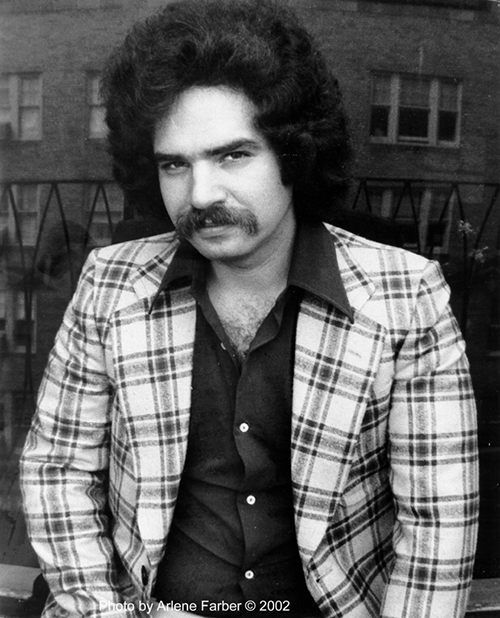

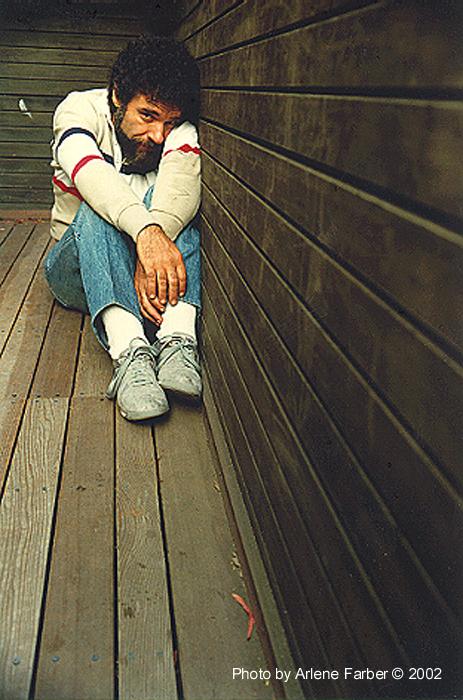

One of the happiest memories I have of Harry Novak is seeing him at a Ray Courts Hollywood Autograph Show at the huge Shrine Auditorium. Novak was dressed in silk suit and tie and was pushing a wheelchair. In the chair sat Sam Arkoff, co-founder of American-International Pictures—a much higher budget rendition of Harry’s own enterprise. Mr. Arkoff could no longer walk as his health was failing in advanced years. I got the impression Sam had never attended such a huge event, and that Harry wanted his friend to see how popular the genre films were among a new generation of young people. Harry called me over and introduced me to his long time friend. I had about 5 minutes to speak to the great man. I asked about his work with Roger Corman, the imported Godzilla films from Japan. Sometimes he had a smile and an answer to my questions, sometimes he just couldn’t recall details from so far back. And soon this precious meeting ended. There were other people at the convention Harry wanted his pal to meet, and he wanted to wheel Arkoff to view the many exhibits on the floor. So they faded into the throngs of fans; I stood and watched as they wheeled on up to the horizon and turned right, Adios. Sometime later, Sam was another veteran an elder movie statesman on his way to heaven. Dear old Harry eventually helped pull together a tribute to Sam for Cult Movies—and it was beautiful. Many believe that at The End, when elements of the body disperse, that the consciousness goes on into a new and beautiful experience. For one of that mind set, the death and dispersal of Sam Arkoff does not seem like a thing of pity or dread; rather an act of love. Such could not be said for the 24-year-long-death of Jerry Gross. Death by causes natural or unnatural; by gross (forgive me) overindulgence? If ever a death and burial of a person could be termed gross, it was the final unreeling of movie dealer Jerry. The first time I saw a Jerry Gross film was when I had to lie about my age to get into a theater ro see a film about Fritz the Cat, an X-Rated cartoon feature where we were supposed to be 18 or over to see it. Later, I learned that Jerry produced and distributed horror films and art house product. Sadly, I’d not seen these. “Mike, I want you and Coco to meet my wife and me at the synagogue tomorrow for the last rites of Jerry Gross.” This was our friend Harry Novak, offering free advice. “Be sure to bring lots of Cult business cards to pass out; you’ll get hundreds of interviews for your magazine. Everyone in the indie film business will be there—in one place—to pay tribute to the late Jerry. You’ll get producers, directors, writers, distributors, acting talent, technicians—all the people in the business! My wife Carmen and I will be there at noon. You bet we’ll be looking for you!” I and my lady friend (and editorial assistant) Miss Coco Kiyonaga, showed up the next day (in her Mercedes sports car convertible). We drove up to the huge place of worship where the funeral was to happen. Her black sports car turned the corner, pulled into the giant parking lot behind the building and we looked at each other sharing the most “uh-oh” moment a couple could have. The spacious lot was vacant, save two cars parked next to the rear entrance of the building. By that door was one woman pacing, crying, hand-wringing—longish hair, elegant in a business suit—without the despair she’d have been beautiful. As Coco and I walked toward the woman we could hear her asking, “When are the people going to get here? When’s everybody going to come?” We stepped up and introduced ourselves as editors from Cult Movies. The lady wasn’t impressed as she’d never heard of our magazine. We were more impressed with the lady, as she turned out to be Arlene Farber; actress and ex-wife of Jerry Gross. She was the one-woman crew that had put this funeral together. She was still on loyal, friendly and loving terms with Jerry, even after years of legal separation.  Arlene Farber in The French Connection Arlene owned one of the cars in the parking lot. The other belonged to the Rabbi. Coco, Arlene and I went inside and sat in the pews as the tension mounted. We sensed the Rabbi knew nothing of the exploitation films of Jerry Gross. If he knew anything about the man, he’d be embarrassed to speak about it. It was, by now, obvious there would be no one showing up to be spoken to. Then came inspiration from Coco. Dave Durston’s phone number was in her cell contacts. She planned to interview him soon because—she had learned—Dave had done theatrical stage work with Bela Lugosi. Synchronicity continued as Dave had also been a business partner of Jerry’s. Dave made I Drink Your Blood, which Jerry distributed. So, picture this—in this holy place: there lie the last remains of Jerry Gross, in his coffin, near the altar. Also near the altar, patiently awaiting its part of the rousing tributes, loving memories, tearful fare-thee-wells—stands a microphone that no one showed up to use. Ever resourceful, Coco speed-dialed Dave and actually caught him at home—sound asleep at half past noon. Coco reminds him who she is and tries to persuade him to come and give Jerry a proper sendoff. After a long pause, Dave said, “Nobody told me he died. And it would take way long to get dressed, you know?” But, while Durston did not make an appearance, following is what did take place. The cell phone was handed to Rabbi Gurman who walked it over to the microphone. The good man of the cloth told Dave Durston that he was free to give as long a service as he wished. Dave got right to the point. “Jerry was a good friend, a great promoter. He was a damned good showman.” All this fills the vast, empty hall, amplified by speakers in the ceiling overhead. The patter-chatter spiraled down to , “I can’t really think of anything bad to say about the guy…” And it was over. The funeral service, like all good things, had come to The End. Arlene Farber and I, along with the Rabbi and his assistant, comprised the 4 pall bearers who carried Jerry in his casket, to the hearse which had joined the 2 lonely vehicles parked at the back door. There was no one to bang the drum slowly, not enough mourners to complete the proper 6 bearers of the pall—it felt as if there should be a thunder storm just then—but It Never Rains in Southern California. By now, Miss Farber was frantic; crying again and wringing her hands. Where the hearse went I don’t know as Arlene didn’t want to go there. She didn’t want to see Jerry being disposed of. The woman did say she was frightfully depressed and did not want to be alone. We took her to a coffee shop and had our own, more personal tribute, to Jerry. I had a cassette recorder and let her talk. What she said became part of the tribute pages to Jerry in Cult Movies. Coco did the interviewing.

It came down to this: Her husband was a great and successful showman who knew what audiences would pay to see. At his peak he always had at least $5 million in personal accounts. He put Arlene in some of his films, fell in love with and married her. They had many good times. Somewhere along the way, his tastes became more expensive. I think she sensed that he was seeing other women and consuming narcotics… she confronted him. The marriage suffered and they divorced but never fell out of love. By 1978, after years in New York, Jerry had settled for good in Los Angeles. His last credit is for that year, as Executive Producer for one episode for the TV show THE WAY IT WAS. After that he dropped from sight. The spending continued, he lost his home in Beverly Hills and took a single room on Skid Row. One of his associates told me that Jerry had developed a severe case of agoraphobia. In its thrall, one is afraid to meet new people and terrified of going out into open spaces lest a crowd of people should engulf you. If that was indeed the case, then Jerry no doubt felt quite secure in his rented room. And he was not entirely alone as Arlene would stop by to see him, bring him food, pay his rent… she cared. Mr. Gross wasn’t broke. He received Social Security after a lifetime of high-end tax-paying. Sometimes he’d walk to cash his check; most often though, not. There is scant information on the internet with regard to Jerry Gross. But to accentuate obvious truth, isn’t the internet something of a grand conspiracy? We read that Jerry died at The Legacy Hotel—or maybe The Continent. It states that he left this life in his early 60s: January 26, 1040 – November 20, 2002. Reports from the Coroner, truth from the internet…we may never know the honest facts at large. As told by Arlene, she saw Jerry at his room one last time—talked on the phone after that, then heard nothing for awhile. When his rent was left unpaid for several months, management entered his room with a passkey. There in the corner lay Jerry, free of his phobias at last and wearing a 3-piece wool suit with uncashed checks stuffed in a vest pocket. Past desire or caring, he’d curled up on the floor and gone to sleep. Forever. There were elements of Jerry’s Final farewell that bothered Miss Farber. After all the paid ads and content Jerry had sent to insider publications Variety and Boxoffice, why hadn’t any of them sent a reporter, or a wreath—or something? The only publication that covered the man’s passing was Cult Movies. To this day, I don’t know why Harry Novak and his lovely wife failed to show, after telling me, “We’ll see you there, tomorrow.”

For a few of Jerry’s smaller releases, he’d handle distribution on the East Coast while Novak handled actual physical distribution on the West Coast. Harry had a very close relationship with Pacific Drive-Ins, so selling the Gross product in California should have been a snap. But no one from Pacific Theaters came to say goodbye. Some of the films may have been reviewed in local papers, but such periodicals as The Los Angeles Times got in line and joined all the others who refused to write a column of condolence—or anything. I told Arlene she had the freedom to design out tribute. She wanted us to put a Gross film title on our cover, I Spit On Your Grave. She felt that was the amount of respect the entire film industry had shown Jerry. She also provided all the photos of Jerry which accompanied the inner text. As things unfolded, Arlene felt the involvement of Cult Movies brought uplift to a dismal affair. There in the synagogue she felt Jerry’s presence and comfort as we sat—almost alone—in close proximity to his remains. She still felt his love. And I sat, showing respect for a film rogue I’d never known in life. Being a girl of the 1960s, Arlene said, “I feel a good vibe coming from you.” When it came to publishing a timeline on Jerry, I was at a loss. I knew few biographical or filmic facts. I turned to our film writer, Joe Wawryzniak, who had a photographic memory for the cinema. He wrote a fine tribute which received a surprisingly large response from our readership—and praise from Arlene. The only slip up was a typo which changed the facts and altered history. Our layout artist couldn’t believe his own eyes, typed in that Jerry was gone 3 days prior to the discovery of his remains. For the sake of tales where only the facts, the honest mortified truth may be told, I’ve dug up my 2002 notes of the case and re-read my own brief editorial on the subject (as it ran in Cult Movies #38). In truth, the empty body of Jerry Gross lay abandoned, slowly turning to a mummy, de-liquefying for 3 months, in his upstairs hotel room. Only then was his absence noticed, his body discovered and rudely stuffed into a body bag tagged “Property: City Morgue” and carted down from the 2nd floor room. (Or was it the 4th?) | ||||||||||||||||