|

|||||||||||||||||

November 2009 Web Edition Issue #3 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Mondo Cult

Forum

Blog

News

Mondo Girl

Letters

Photo Galleries

Archives

Back Issues

Books

Contact Us

Features

Film

Index

Interviews

Legal

Links

Music

Staff

|

A Brief Word from the Editor...Happy Birthday Ray Harryhausen. On June 29, you would have turned 98 years young. Yes, I do say young. I had the pleasure of meeting Ray several times over the years, but our first meeting is one I will never forget. We were in his hotel room and he was showing me his goodies. Goodies that consisted of Medusa and her pals. He had the original pieces with him and would do a show and tell on a panel later that day. Ray let me hold Medusa. She was always my favorite. But, as he was pulling them out of their packing, and placing them on the table in front of me, I was watching him closely. He had a smile on his face that reminded me of a young baseball fan, pulling out his treasured card collection. His eyes were shining and he was bouncing around on his chair. When they were all lined up he looked at me and said, "What do you think?" I said, "I think you're about 8 years old!" At this he laughed out loud and said, "Well. Yeah!" The joy on his face that day came flying back to me full force, as I was reading L.J. Dopp's article. That same joy on Ray's face comes pouring forth from this article, as the fan remembers. Enjoy. * * * Ray HarryhausenA Fan’s Remembrance

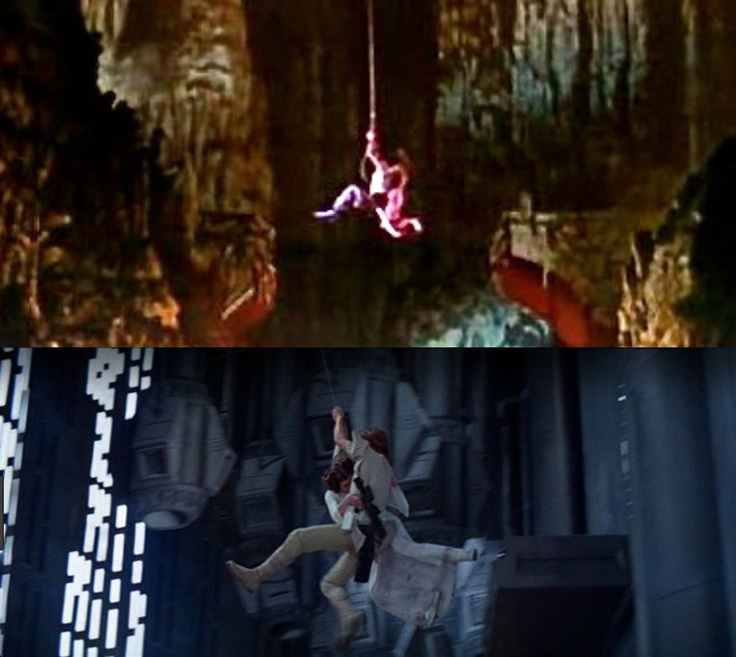

by L.J. Dopp* * *A CHILD, FOREVER CHANGEDSaturday afternoon, January 3rd, 1959, I accompany my friend from up the block and his father to the Los Feliz Theater in Hollywood, California, about a mile from the hospital where I was born. After the cartoon and trailers, writing on the screen announces the main feature is beginning. Suddenly, wonderfully exuberant, Arabian-themed music (by Bernard Herrmann) blares over the Columbia logo and titles, which declare the movie is “Filmed in Dynamation, the New Miracle of the Screen.” During the title sequence the camera pans over a colorful, illustrated map, featuring characters from the film drawn in the ancient Persian style. “Is the whole movie a cartoon?” I ask my friend’s dad, and he says, “No! Shhh!” These are the last words any of us speak until the movie’s end – no popcorn or bathroom trips required during The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. When the Cyclops came running out of that cave chasing the magician, Sokurah (Torin Thatcher), at the beginning of the movie, my life was changed forever. I‘d seen Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (1954), The Ten Commandments (1956), and other Disney features in theaters, but we had a black-and-white TV, and I had never seen anything like this Cyclops. At age 7, I didn’t wonder how it was done; the creature looked absolutely real to me – as did the movie’s 2-headed Roc, dragon, and sword-fighting skeleton. I’d seen Ray Harryhausen’s animated dinosaurs in Irwin Allen’s The Animal World (1956), but they didn’t capture my imagination like the Cyclops. Eventually, I would learn about Ray and his mentor Willis O’Brien from the pulp pages of Famous Monsters of Filmland. Of the many times I have seen 7th Voyage, the most interesting viewing was in 1972. During my years in Los Angeles City College’s Theatre Dept., I had become friends with Mark Hamill, and he loved the film too, being a big sci-fi/fantasy fan. He rented a 16 mm print and a projector, and invited me to watch it at his apartment near school, along with our girlfriends. This was five years before the home video revolution and Star Wars; Mark was on General Hospital at the time. Gratified, I was, to recognize a key scene from 7th Voyage lifted by Star Wars five years later. During their escape from Sokurah’s cavern, the Genie (Richard Eyer) produces a magic rope so Sinbad can swing across a gap in the rocky span, biding Parisa (Kathryn Grant) to “Hold on tight, Princess!” Luke Skywalker is considerably less romantic with Princess Leia, when he swings with her on a cord he deploys like Batman, over a walkway gap in the core of the Death Star. Even the diagonal streaks of light on the left cavern wall in 7th Voyage seem to be suggested in the Star Wars scene.  The 7th Voyage of Sinbad & Star Wars' "princess" rope swing.

This is a perfect example of the “snowball effect” Ray mentions in the documentary, It Came from Ray Harryhausen (created for Sony Movie Channel’s 2011 RH festival), when discussing the influence his films have had on other filmmakers like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Peter Jackson. The screenplay for 7th Voyage is credited to Kenneth Kolb, but it’s based on the Arabian Knights adventures, and more specifically, on the storyboards Ray created to sell the idea. The island of Colossa is actually Mallorca, and Bagdad is the Alhambra Palace in Granada, a remnant of the Moorish occupation. So, Bagdad is a seaport, and Sinbad’s ship is a three-masted frigate in some stock shots? …Details. Still not knowing his name, I recognized the quality of Ray’s work in The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960), again starring Kerwin Mathews and directed by Nathan Juran, but seemingly aimed more at children than 7th Voyage had been. Ray’s touch is more obvious in Mysterious Island (1961), Verne’s sequel to 20,000 Leagues. His Nautilus is a reasonable follow-up to Disney’s sub in the 1954 film – especially considering Disney’s Nautilus had a separate copyright for its Harper Goff design, including the silhouette. These early color-stock budgets were afforded, in part, by implementing public domain stories from mythology or classic literature, but the art direction on Harryhausen productions was always top-notch. He was not just a visual effects maestro, made executive producer by clout; Ray Harryhausen was a filmmaker – as proficient, creative, and influential as Disney – at least, to many of us. And, Ray did all the storyboards and animation on his films by himself, moving his models one frame at a time, and in the early days, with only one assistant to advance the camera. His artistry is all over his work, exactly like Disney’s was when Walt was alive. Putting Captain Hardy’s (Michael Craig) voice-over narration through an echo chamber adds an ethereal quality to Mysterious Island, as does the haunting Bernard Herrmann score. It’s one of my favorite RH movies because of its atmosphere; a scene where the castaways cross a log bridge over a misty waterfall while Hardy narrates against Herrmann’s dissident chords still sticks in my mind. The many colorful, oversized props, brilliant matte paintings, and underwater photography, add to the “mysterious.” Shot in Shepperton Village Square because it resembled American Southern architecture of the time, the escape by balloon from a Civil War prison camp during a storm provides another of Harryhausen’s best openings, but one of the most exciting sequences for me is the battle with a giant crab the morning after they land, which the men boil in a volcanic sulfur pot, and eat. Formerly blacklisted American expatriate, Cy Endfield (Zulu), directed, and the pace never lets up on this island – actually Spain again.  This dry-docked Nautilus is captained by Herbert Lom as a sympathetic Nemo, and the rest of the marooned cast includes Gary Merrill, Joan Greenwood, Michael Callan, Percy Herbert, and Dan Jackson as a dignified African American. His “Ned” character is treated as an equal – eventually, even by the one Confederate (Herbert); and, considering the era depicted, that idea that Ned was not made to act subservient to the whites – including a titled Englishwoman played by Greenwood – was ahead of its time in 1961 American cinema, two years before the Civil Rights Act would be passed. Nemo’s motive for introducing giantism to the flora and fauna of Mysterious Island is also more topical today: he no longer wants to blow up warships, but instead, attacks the very cause of war – world hunger. By the time I saw Jason and the Argonauts (1963) at the Roxy Theater in Glendale, with 7th Voyage as its co-feature, I was aware of stop-motion animation, Ray, and Willis O’Brien. As we exited the theater, my friend from up the block said, “Well, that was pretty good, but I still like Sinbad better,” and so did I. Jason is technically a better film, but I wasn’t seven years old anymore, and I knew the creatures were models moved one frame at a time. I had also read every Arabian Nights or mythological adventure I could get my hands on, hoping to recapture the excitement I felt the first time I saw the Cyclops run out of that cave. So, by Jason’s debut, I knew Medea (Nancy Kovak) would marry Jason (Todd Armstrong) and become the poster girl for bad parenting, and I missed the true-romance-that-can-never-be plot of 7th Voyage. Sinbad and Parisa could never really be happily married with her only six inches tall; she had to be restored to full size. Some of the world’s greatest movies feature a true-romance-that-can-never-be (Gone with the Wind, Casablanca), but few have the wife-who-murders-the-kids-and-runs-off element that would befall this fleecy couple, according to Greek mythology. While not big box office at the time, Jason is considered by many to be Ray Harryhausen’s greatest film. Ray had improved his Dynamation process by Jason, his fifth color feature, and it has incredible location photography by Wilkie Cooper which includes a myriad of eye-popping animated creatures. The sequences with Talos, the Hydra, and, a half-dozen skeletons attacking Jason and his crew, rank with the best of his work.  The south of Italy near Naples provided the white sandy beaches, rocky terrain, and Greek temples needed to film Jason,as the Greeks had colonized Italy before the Romans; e.g., the temples at Paestum were used in the background of the harpy sequence. But, filming in Italy during that bustling era had its downside; they weren’t the only crew shooting there. As Ray explains in his 2004 autobiography, Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life (by R.H. & Tony Dalton; Billboard Books): “…We were shooting a scene in which Jason’s ship, the Argo, was to appear around a rocky bluff. Everything was ready, the camera was rolling and we radioed the ship to start off. What should come around the bluff but The Golden Hind! The tension was broken when Charles was heard to shout, ‘Get that ship out of here! You’re in the wrong century!’ …Another British film crew was shooting some second unit footage for the TV series, Sir Francis Drake, and their ship had more power, and beat ours around the cove.” The Argo itself was built for Jason around a barge with three Mercedes Benz engines. Its $250,000 cost was offset by Schneer’s later sale of the craft to Fox, for use in Cleopatra’s battle of Actium. Armstrong (Walk on the Wild Side) and Kovak (Diary of a Madman) were Columbia contract players, but the rest of the cast was mainly British. Laurence Naismith and Nigel Green assay the roles of Argonauts, while Honor Blackman (Goldfinger) plays the goddess Hera. She aids Jason from her cumulous digs on Mt. Olympus, while Zeus, played by Niall MacGinnis (Curse of the Demon), moves figurines of Jason and his ship around on a chessboard of the gods. When Jason beckons Hera for help, he speaks to her carved effigy. Ray explains in his book: “The Hera figurehead, located at the stern of the vessel, was designed so that the eyelids opened and the eyes moved, but I drew back from making the mouth move, as I felt that most audiences would liken it to a ventriloquist’s dummy, and it would then become borderline comedy. In the end we decided that Hera would communicate with Jason in his mind.” The Bernard Herrmann score is absolutely Olympian, too – one of his best. There is not enough room here to credit all the writers on Harryhausen’s movies; some scripts were completely re-written by other teams of writers. But the stories were based on Ray’s production drawings, with “step-plot” outlines linking them, mutually conceived in “sweatbox” sessions with Ray, Charles Schneer, and the writer(s) at hand. On Jason, Beverley Cross was brought in because he was an expert on Greek mythology. After the production wrapped, Ray married Diana Livingston Bruce on October 5, 1963, and their marriage lasted 50 years, until Ray’s passing on May 7th, 2013. They had one daughter, Vanessa. Columbia Pictures submitted Jason and the Argonauts for a Best Special Effects Academy Award ® for 1963, but it wasn’t even nominated. What did win? Cleopatra – with the Argo in its biggest FX sequence! By this time, I was discovering Harryhausen’s black-and-white movies on television, each one a treasure unto itself. IN THE BEGINNINGRay Harryhausen was born June 29th, 1920, in Los Angeles, California. Along with Ray Bradbury and Forrest J Ackerman, Harryhausen was a member of the Los Angeles chapter of Hugo Gernsbach’s “Science Fiction League,” founded in 1934, which met for a time in Clifton’s Brookdale Cafeteria on Broadway near 7th Street. Led mainly by Ackerman in 1939, it split off to become the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, but the three men would remain close friends all their lives.  The Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society convenes at Clifton's Cafeteria.

A young Ray Bradbury sits two from the left; Forrest J Ackerman, "Number One Fan," sits to his left. Robert A. Heinlein, with mustache and glasses, sits five from the right; and Jack Williamson stands six from the right. © L.A.S.F.S., Inc. Ray’s greatest inspiration growing up was provided by the stop-motion films of Willis O’Brien, particularly King Kong (1933), which Ray had reportedly seen 90 times by the 1960s. He got to work with “Obie,” as O’Brien was called by his friends, on Mighty Joe Young (1949), co-produced by Kong’s Merian C. Cooper, along with John Ford. Kong’s co-director, Ernest P. Shoedsack, helmed Joe. The young Ray had been a frequent visitor to O’Brien’s RKO effects shop before WWII, during which Ray made documentary films for the Army Special Services Division in Frank Capra’s unit. In fact, it was a call from one of his wartime Capra contacts in the mid-fifties that brought Columbia producer Charles Schneer into his life. But before he would team with his greatest collaborator, 33 year-old Ray Harryhausen would make his solo, animated feature debut. Again, from his autobio: “Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) had brought O’Brien’s The Lost World (1926) into the atomic age, and was the first ‘monster-on-the-rampage’ movie of the 1950s, inspiring the Japanese Godzilla cycle and establishing the basic formula which subsequent ‘monster’ films were to duplicate.” Not bad for a first solo effort. Based on a short story by friend, Ray Bradbury, Beast was a huge hit, and typecast Harryhausen as an animator of dinosaurs – a role he would cement three years later working with his mentor, O’Brien, on the brief, stop-motion dinosaur segment in The Animal World. The fiery finale of Beast is set on Coney Island and has the titular creature destroying the roller coaster – mostly in miniature – but the live matching shots were done on the dual-track Cyclone Racer at California’s Long Beach Pike. Ray had also been making stop-motion animated shorts based on classic fairy tales since the ‘40s, and had long held the idea for a feature based on the Arabian Nights. From An Animated Life: “Whilst thumbing through some of my Gustave Dore illustrated books, I came across an engraving of a knight atop a broken spiral staircase. Struck by its very dramatic pose, a rather melodramatic thought occurred to me: why not have the Knight fight with a living skeleton (a form I had long wanted to animate)? …I had always been intrigued by the Arabian Knights stories, and decided that the character of Sinbad, as the personification of fantasy adventure, would fit the bill as the skeleton’s adversary.”  The 7th Voyage of Sinbad storyboard by RH.

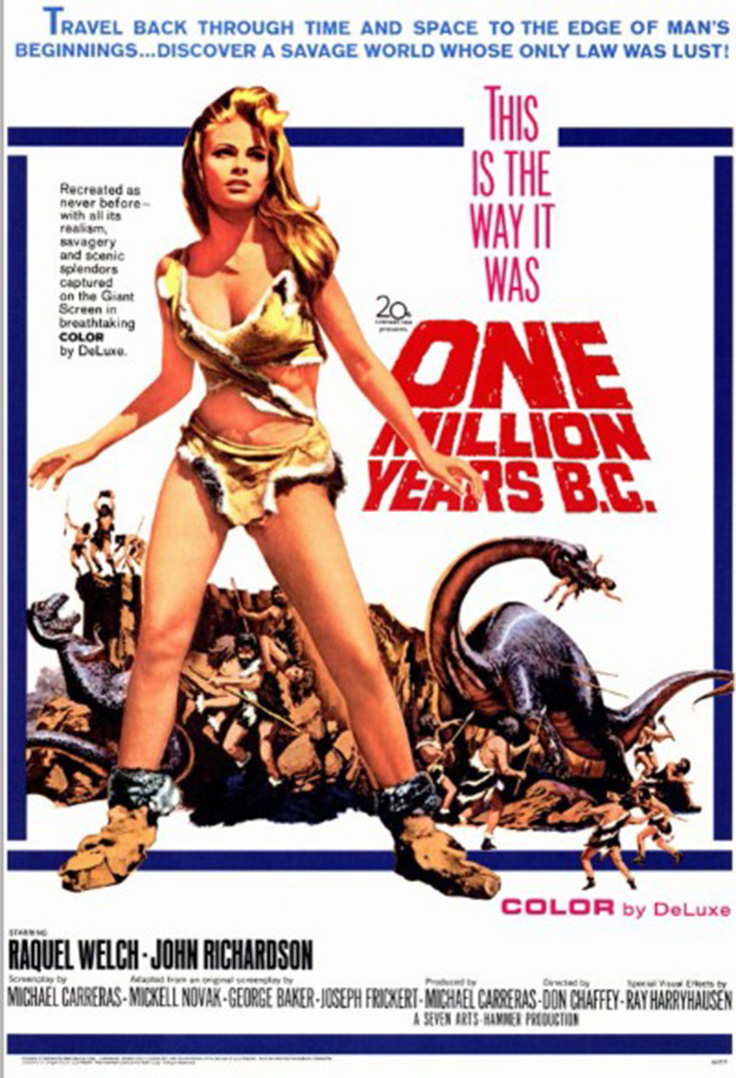

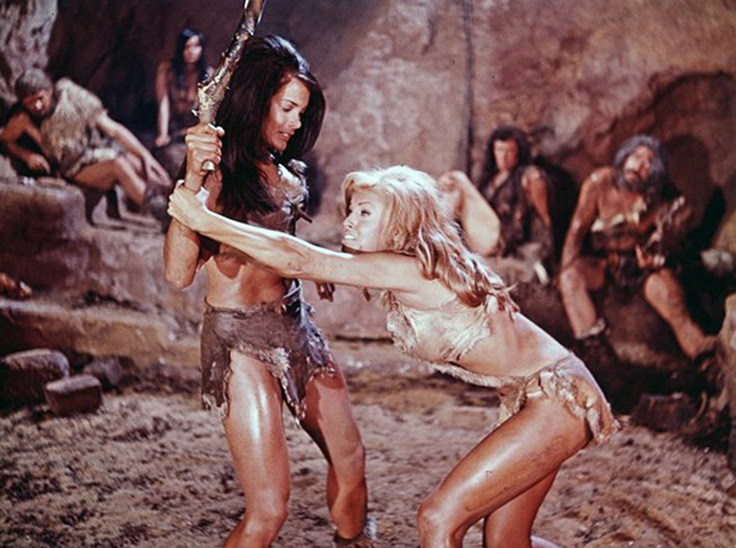

His storyboard drawings for Sinbad remain some of his best illustration work – and he was a magnificent artist. The Art of Ray Harryhausen, a coffee table book full of his production drawings, was published in 2006 (by R.H. & Tony Dalton; Billboard Books). Before Schneer came along, Ray tried to sell the Sinbad idea to other producers: George Pal was too busy, Jesse Lasky, Sr., didn’t know what to do with it – and, Ray couldn’t get past Edward Small’s secretary. Later, when The 7th Voyage of Sinbad became a big hit, Small so regretted his passing on the project that he mounted his own ripoff movie, Jack the Giant Killer (1962), snagging Kerwin Mathews and Torin Thatcher from the 7th Voyage cast, as well as director, Juran. But, in the absence of Harryhausen, Small hired Jim Danforth to animate Wah Chang’s sculpted models, and the magic that had surrounded the creature effects in 7th Voyage was conspicuously absent. A musical version of Jack the Giant Killer, labeled “ersatz,” in Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide, has the actors’ mouth movement sped up and reversed to make it seem like they’re singing the songs, added later. Recently, Jack has been treated to a first-class remake in Jack the Giant Slayer (2013), so the Harryhausen snowball effect is not likely to diminish in our lifetimes – even from films simply inspired by his movies. But, before the Sinbad character would materialize on color film stock in 1958, three more black-and-white epics of nuclear-or-alien creatures wreaking destruction would come, all produced by Charles H. Schneer and released by Columbia. Ray always insisted his animated creations were “creatures,” not monsters. It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), and 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) devastated San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Rome, Italy, respectively. The first movie featured a giant octopus and Kenneth Tobey (The Thing), but the flying discs in the second film were used again by Columbia in The 27th Day (1957), and inspired Tim Burton’s saucers in Mars Attacks (1993). Earth vs. the Flying Saucers was produced by “Jungle” Sam Katzman and directed by Fred F. Sears, a former actor who’d worked on Charles Starrett’s western film unit for Katzman. Its special effects dwarf those of the duo’s 1957 production, The Giant Claw, which does include some left-over effects from Earth. According to Richard Harland Smith of Turner Classic Movies, Katzman had planned to hire Ray to provide a stop-motion creature for Claw, but budgetary constraints forced him to hire a model-maker from Mexico City instead, who provided a ludicrous “marionette” that The New York Times later compared to Warner Bros.’ cartoon character, “Beaky Buzzard.” An apocryphal theory regarding 20 Million Miles to Earth suggests its bipedal Ymir creature had its armature cannibalized to make the Cyclops in 7th Voyage due to the Ymir’s latex having rotted away. Not true: the Cyclops was built on a larger scale than the dragon in 7th Voyage, so when they had to fight, Ray used the armature from the Ymir to make the second Cyclops, because it was smaller. That Cyclops also has a second, smaller horn, behind the first. SELENITES AND MORE DINOSAURSAfter Jason and the Argonauts, the next release from Ray and producer Schneer was H.G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon (1964). British character actor, Lionel Jeffries (The Revenge of Frankenstein), plays inventor Joseph Cavor as a charming but dotty eccentric. He’s horrified by the equally English Edward Judd’s (Island of Terror) violent treatment of the Selenites, as the native Moonies are called, after a first encounter of the worst kind. A giant centipede with glowing red eyes tops the brief list of animated effects, including a few key Selenites and Martha Hyer glimpsed as an animated skeleton when pacing behind an X-ray screen.  On First Men, Harryhausen had a big problem revamping his Dynamation process for super widescreen: a special anamorphic lens provided by Panavision proved useless. He compromised, and filmed the animation scenes as traveling mattes, due to budgetary restraints. Subsequently, several animated sequences were lost and do not appear in the film. Bernard Herrmann had raised his rate, so they hired British composer Laurie Johnson (TV’s The Avengers), who did a creditable job. While short on creatures, First Men is one of the most beautifully designed of Ray’s films, due in part, perhaps, to director Nathan Juran, called “Jerry,” in Ray’s book. Juran had been “Nathan Hertz” in Europe, and was a well-known production designer and art director (How Green Was My Valley), who had also helmed 20 Million Miles and was largely responsible for the riot of colors in 7th Voyage. Having made a few films, I continuously marvel at the many patches of different-colored lighting Ray got in his cave scenes. Both Sokurah’s cavern in 7th Voyage, and the gorgeous lunar caverns seen here, are awash in brilliant colors that could only have been cast by hidden 2K or 5K lamps, as CGI hadn’t been invented yet. First Men’s sets were built at Shepperton Studios, but generators had to be employed for many 7th Voyage locations; Sokurah’s cavern, e.g., was located in the natural Caves of Arta on Mallorca, and filming there was limited to one day-and-night for the entire film!  The classic photo of Raquel Welch in the fur bikini on the poster for One Million Years B.C. (1966) was not taken in a studio photo session. A location shot by the unit still photographer, captured in natural sunlight, ended-up looking the best. It’s the only remake Ray ever agreed to do, and also the only one of his films I can think of that used live animals as giant creatures. An iguana and tarantula are enlarged with special effects, which was Ray’s idea, thinking that having seen real creatures in the beginning, the audience would believe the animated dinosaurs were real, too. Michael Carreras of Hammer Films felt that his studio needed to explore new areas besides horror, and had acquired the rights to Hal Roach’s caveman/giant lizard epic, One Million, B.C. He approached Harryhausen about doing the dinosaur effects, who at first didn’t want to do a remake, but loved the idea of animating more dinosaurs. Ray saw the possibilities after a screening of the 1940 version – so, was loaned-out to Hammer from Charles Schneer’s company, Morningside Productions. One Million Years B.C. was a Hammer/Seven Arts film, but a 20th Century Fox release in the U.S. – hence the casting of Raquel Welch, whom Richard Zanuck was promoting, as earlier that year she had become a star off the Fox hit, Fantastic Voyage. It was the first Harryhausen film since “Animal World” not released by Columbia and not produced by Schneer. Stark, volcanic rock locations were found in the Canary Islands, and Don Chaffey, who had helmed Jason, directed. Martine Beswick of the rock people tribe has one of her patented girl-fights (From Russia with Love, Prehistoric Women) with our bleached blonde from the shell people tribe. They tangle over leading caveman, John Richardson (Black Sunday, She), who along with the rest of the cast, does a good job, especially with unintelligible dialogue.  Martine Beswick and Raquel duke it out, old-school.

The next movie for Harryhausen and Schneer was a tribute to Ray’s mentor, WiIlis O’Brien. Before Ray went into the army in the ‘40s, he stopped by OBie’s RKO special effects department and saw the dioramas for his mentor’s new project, Gwangi, an Indian word for lizard (pronounced gwan-gee). Sadly, OBie’s project never got made, along with his ill-fated War Eagles, but in 1967, Charles Schneer obtained the rights to the Gwangi story, and it was rewritten from being a contemporary 1940s period adventure into a turn-of-the-century western titled, The Valley of Gwangi (1969). Maybe because they didn’t distribute the hit, One Million Years, B.C., Columbia passed on Gwangi, but Warner Bros–Seven Arts was interested. An agreement between them and Morningside Films was struck, and after thirty years, OBie’s film was finally green-lighted. Set in a nebulous area of Mexico, once again Spanish locations were sought for their excellent production values, and their proximity to Ray’s animation studio at Shepperton. The exteriors were filmed around Almeria and Cuenca, with interiors shot in a Madrid TV station. Rays says that the number of extras who would show up varied from day to day, accounting for the sparsely-populated streets during Gwangi’s escape from the bullring. To me, this never looked like a period picture – the key costumes seem too 20th Century dude-ranch, and I almost expect to see cars and trucks on the streets. Very few location sets were needed, and a shrouded cage, displaying “Gwangi the Great” after he’s captured, is a direct homage to King Kong. Likewise, a scene where cowboys on horseback rope the huge reptile is admittedly lifted from Mighty Joe Young. Ray said the roping scene was the main reason he wanted to do the movie; it had already been story-boarded by O’Brien for his 1939 production of Gwangi, and was lifted from that for Joe. The titular character became a cross between an allosaurus and a T-rex, which Ray referred to as a “tyrannosaurus al.” Gwangi is a fast-moving T-al, and very well done, but it is a tiny prehistoric horse called an “eohippus” that steals the show.  Willis O'Brien at RKO in 1939 with Gwangi "roping" storyboard.

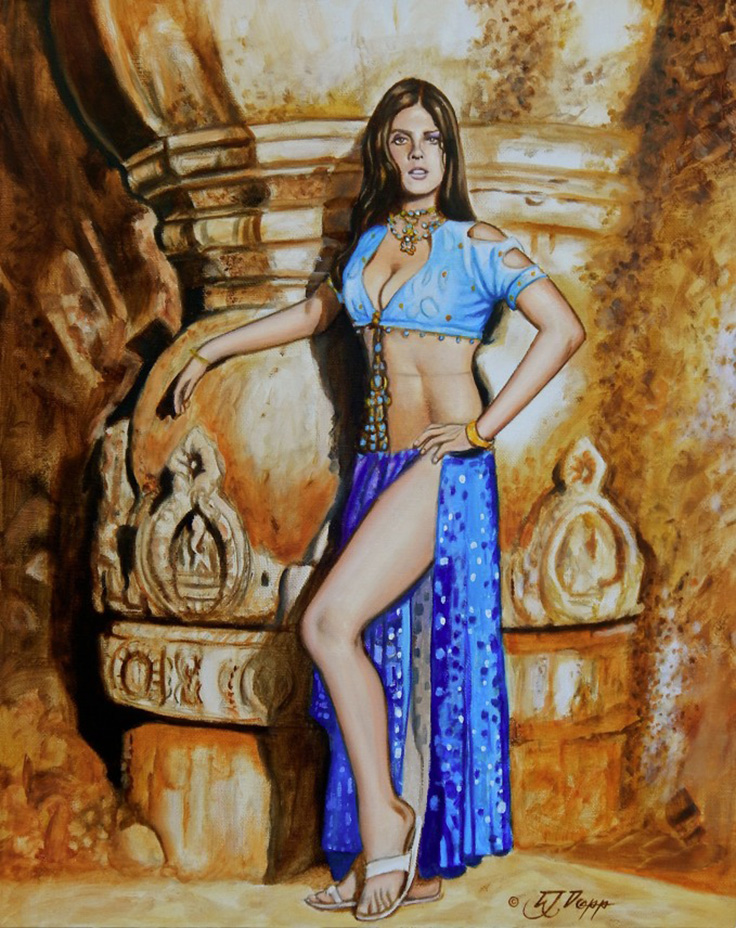

James Franciscus was cast in the lead role, opposite circus owners Gila Golan and the redoubtable Richard Carlson (It Came from Outer Space, Creature from the Black Lagoon). British character actor Laurence Naismith once again lent his charm – as a doting professor of paleontology, the only new character added to the revised script. He’s also the only character interested in keeping the prehistoric creatures in their eponymous hidden valley, other than the Mexican-Gypsy-Indians who live there, and fear the Curse of Gwangi. Naismith is crushed to death when Gwangi escapes his stage-cage à la Kong. Ain’t no justice in this giant lizard western, but Ray’s Jurassic era creatures are pretty cool. What did Ray think of the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park? An artist friend told me in the ‘90s that he’d run into him in a British Bookstore and had asked that question. This is hearsay, but Mr. Harryhausen reportedly stated that in his opinion, those big tails were too heavy to swing around, and were meant to drag on the ground for ballast.  Caroline Munro from The Golden Voyage of Sinbad.

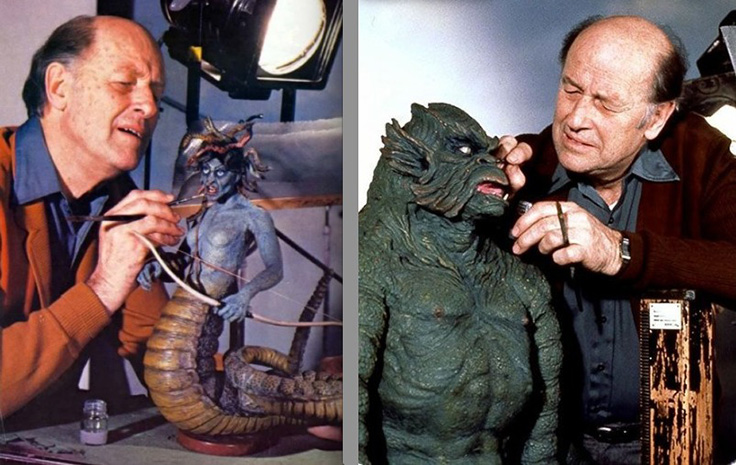

SINBAD AND THE GODS RETURNThe last two Sinbad movies merge in my mind, with peaks and valleys from each standing out. The casting of Caroline Munro in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973), is surely one of the peaks. Her beauty and considerable charm – along with the coast of Spain, once again – provided Ray’s next film with spectacular production values. In 1963, he’d created new Arabian Nights production drawings, but it was not until March of 1971 that he submitted a rough step outline to Charles, called Sinbad’s 8th Voyage. Many of Ray’s ideas remain in the final film, e.g., his villain is called “Jaffa,” after Conrad Veidt’s vizier in Alexander Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad. In the storyboards Jaffa resembled Veidt, even before Tom Baker was cast in the role because his eyes reminded Ray of Veidt’s. For the screenplay, Schneer brought in Brian Clemens, who had a reputation as a writer in the fantasy genre (Captain Kronos, TVs The Avengers). More “sweatbox” sessions ensued with the three of them hammering out the plot by linking together Ray’s production drawings, and in May of ’71 Clemens turned-in a revised step outline titled Sinbad in India. By then, the vizier had become a sympathetic character, with a disfigured face hidden beneath a gold mask. Ray also had the idea of an ape being transformed into a human – it was in Clemens’ first outline – but that element, along with a giant carved face, would be saved for the film to follow. John Phillip Law (Barbarella) was cast as Sinbad, and Caroline Munro had been the female lead in Clemens’ earlier Hammer production, Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter. British actor Douglas Wilmer, who had played Pelias in Jason, lent statuesque nobility to the disfigured vizier. Ray has said that director Gordon Hessler (The Oblong Box) was a joy to work with, bringing many ideas and much energy to the project. Best of all, he was very cooperative when Ray would have to step in to direct the actors in live-action sequences that were to match his later animation. No-one but Ray knew exactly how the actors had to move in those scenes, so in reality, Ray Harryhausen directed many scenes in his films. But, not all of his directors were as cooperative as Hessler, who had worked with Alfred Hitchcock on the latter’s TV show. The score by Miklos Rosa was first rate as well; and for all of this film’s wondrous creatures, a tiny, winged homunculus has the most personality. The Golden Voyage of Sinbad was a smashing, world-wide success for Columbia Pictures. Critics and audiences loved it – but, still no special effects nomination from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences®. The film was submitted, but the judges thought the six-armed Kali creature was a full-sized mechanical statue(!) While several story ideas were discussed for the next film, including Conan, The Hobbit, Skin and Bones, and The Food of the Gods, Ray had this to say about their decision: “…When the popularity of Golden Voyage became apparent, both Charles and I realized we were going to have to make another Sinbad adventure. As luck would have it I had the perfect story.” Beverley Cross was brought back to develop that story, and another formerly blacklisted American who called England home after the HUAC hearings would direct. Sam Wanamaker was tabbed to helm Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977), with its leftover elements from Golden Voyage. The plots of all three Sinbad movies concern the restoration of a human being: tiny Princess Parisa in 7th Voyage; the vizier’s face in Golden Voyage; and, in Eye of the Tiger, a prince who’s been transformed into a baboon. Instead of trying to work with a real baboon, Harryhausen chose to animate a model, which plays chess with Taryn Power during the voyage. John Philip Law wasn’t cast again, in part because Columbia wanted a different Sinbad, and Ray and Charles didn’t want this to look like a sequel. Many actors were considered; including Ron Ely, Michael York, Jan Michael Vincent, Timothy Dalton, Robert Conrad, Terrence Hill, Franco Nero, Joseph Bottoms, and even Michael Douglas (as a white-collar Sinbad?) Patrick Wayne was finally chosen, son of The Duke, and since Taryn Power was the daughter of Tyrone Power, this seemed appropriate. The breakout star was the young Jane Seymour, cast as Sinbad’s love interest. Though not one of Ray’s favorites and labeled too corny by the press, Eye of the Tiger made its budget back fairly quickly. In its wake, Ray and Charles decided they needed to change subjects once again as Star Wars had opened in ’77 and science fiction was all the rage. Although not a hit when released, Jason had gained momentum by the late ‘70s, and was already being considered a classic; so, a return to Olympus was in order, and fortunately, Beverley Cross had been working on such a script for some years.  Ray with the oversized Gorgon and Kraken models from Clash of the Titans.

Clash of the Titans (1981) was the grand finale for Ray and Charles. It was the most lavish of their films and had the biggest budget. Featuring wall-to-wall visual effects and fantastic creatures, this story of Perseus and Andromeda has also been the Harryhausen movie most frequently shown on television. The animated cast includes Medusa, Pegasus, giant scorpions, the evil Calibos, and the towering Kraken. The Medusa scene is particularly suspenseful; the model was very large for a humanoid figure, to allow better expression and movement of the snakes, and the Kraken model was Ray’s largest. An animated, mechanical owl that rotates its head and bleeps is a nod to R2D2 – and we’ve come full circle, as Harryhausen “homages” a character from Star Wars, the movie that “homaged” a scene from 7th Voyage. Also, the key animator from the 7th Voyage knock-off, Jack the Giant Killer, Jim Danforth, was hired as one of Ray’s two assistants for this MGM release. Clash of the Titans’ A-list cast features Laurence Olivier (Zeus), Claire Bloom (Hera), and Ursula Andress (Aphrodite) – who had an off-screen relationship with Harry Hamlin (Perseus) that eventually produced Dimitri Hamlin (son). The added luster of Burgess Meredith, Sian Phillips, and Maggie Smith (wife of Beverly Cross), helped insure box office success. “Release the Kraken!” has become a buzz-phrase in our lexicon for exhibiting gusto, solely due to this film, which begat a dull remake in 2010. In it, Perseus (Sam Worthington) wears a plain sackcloth tunic when not wearing dark armor; in fact, the film’s monochrome palette fully explores the color brown. Liam Neeson’s Zeus could get away with chewing up Mt. Olympus had Ray Harryhausen designed it, because the set still would have upstaged him. My favorite moment in the remake is when Perseus is choosing weapons from the armory for the voyage – there’s always a voyage – and finds the annoying mechanical owl from Ray’s original Clash, lying inert. His companion squints dubiously at the thing for a second… then tells Perseus to “leave it.” AD INFINITUMIn 1992, Ray was awarded a special Oscar®, “The Gordon E. Sawyer Award.” It was presented to him by Ray Bradbury and host, Tom Hanks, who said to the audience, “Some people say Casablanca or Citizen Kane… but I say Jason and the Argonauts is the greatest movie ever made!” And, as to living proof of the snowball effect, the excellent documentary, The Sci-Fi Boys, produced by Paul Davids (Roswell, The Life After Death Project) in 2005, is a chronicle of Ray and his life-long friends, Ray Bradbury and Forrest J Ackerman, and of the “monster kid” filmmakers they have influenced. Interviews with Peter Jackson, Rick Baker, Dennis Muren, John Landis, William Malone, and others who have fueled our fantasies, grace this inspiring documentary DVD; a second disk is filled with early home movies by the budding filmmakers. Also in 2005, Ray was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame – the first year non-literary contributors were honored. If you are a Harryhausen kid your favorite RH film is probably based on how old you were when you first saw it. Those of us who grew up watching these movies still get a thrill when we see that stop-motion movement, often called “jerky.” Even as I got older, the thrill of seeing Ray’s and other animators’ stop-motion effects never wore off. During Star Wars, the theater audience gasped appreciatively at the animated chess game aboard the Millennium Falcon, and when Luke Skywalker rode into the rebel headquarters on a tauntaun at the beginning of The Empire Strikes Back, the audience burst into applause. It seemed to me that they were applauding the stop-motion animated creature he was riding as much as Luke Skywalker’s entrance; the snow walkers in Empire were stop-motion as well. But, that was nearly forty years ago. Modern audiences require state-of-the-art computer generated imaging (CGI), and one movie’s SFX looks much like the others’. While directors like Tim Burton, Guillermo Del Toro, and J.J. Abrams still have their unique styles – as do key makeup designers like Greg Nicotero (The Walking Dead) – many modern fantasy films lack the personality that Ray’s old movies had. I was honored to meet Mr. Harryhausen a couple of times, tell him that The 7th Voyage of Sinbad is my all-time favorite movie, and even have him do a brief cameo in The Boneyard Collection (2012), an anthology feature I designed, and co-produced with director, Edward L. Plumb. Boneyard is hosted by Ray’s old friend, Forry Ackerman, and Ray plays himself being interviewed in the back of a limo by Mondo Cult publisher, Brad Linaweaver, talking about how he moved actors around the set like chess pieces, in reference to Zeus in Jason. And, that’s how I like to think of Ray, now – like Zeus up in Olympus, still touching our hearts and minds with the mythical creatures in his films, and through that ongoing snowball effect. I thank the gods for having been born when I was, for my love of Ray’s unique artistry, and for still getting that thrill when I see the “jerky.” L.J. Dopp is a Sherman Oaks, California, based artist-writer who has made a few films

and also did the above Cyclops and Caroline Munro paintings. © 2018 — L.J. Dopp |

||||||||||||||||