|

Editor’s Note: The following article first appeared in Wonder #11 in the summer of 1995. Wonder, you’ll recall, is proudly touted as “the children’s magazine for grown-ups”. Author Brad Linaweaver was honored to have his article presented as the cover feature then and is still grateful for the faith Rod Bennett and Lint Hatcher had in him as we at Mondo Cult make this article available again.

— Jessie Lilley

Val Lewton

Val Lewton

Spiritual Terror

The Horror Films of Val Lewton

He Made Horror Movies

for People Who Don’t Like Horror Movies

by Brad Linaweaver

When I first discovered WONDER Magazine (my first was #3, the one with This Island Earth on the cover) I noticed that the magazine wasn’t only about movies, but that here was a periodical I could count on to give loving coverage to my favorite films. I was also impressed by WONDER’s editorial philosophy. To argue that the traditional values of Western Civilization have a lot to do with the Sense of Wonder often found in popular art is a daring approach. This outlook may be downright crazy for a publication fighting for a share of the nostalgia market...but then again, nostalgia may be the last place where these values have a chance.

One thing is for certain: many of the older films speak to something in us that a whole bunch of modem films have forgotten how to address. The truth of this can be seen when current filmmakers try to remake the good stuff. In the area of the horror film, there has always been a sizable audience that prefers shadows to blood. There is also an audience that enjoys graphic carnage. Many able filmmakers today try to satisfy both tastes, but the result can often be a schizophrenic production. More promising results might be achieved if films went all one way or the other, with the recognition that today's market can reward both approaches.

For those who want to try their hand at subtlety and suspense, there’s a handful of old horror movies that did everything right. The timing was perfect. The lighting was high art. The characterizations always rang true. The master of suspense cinema, Alfred Hitchcock, respected the modestly budgeted horror films made for RKO in the 1940’s by producer Val Lewton.

There is nothing new about recognizing Lewton’s achievement. His work has been analyzed by many of today’s top imaginative writers, from Stephen King to Harlan Ellison. Books and essays have been devoted to the subject, including a thorough job by Joel E. Siegel, Val Lewton: the Reality of Terror (The Viking Press). Directors who worked with Lewton always gave credit to the man’s reliable good taste and cinematic instincts. One of the most respected film critics, James Agee, recognized that the Lewton productions were doing something special back when the pictures were brand new and being sold as exploitation product. The Lewton legend has been carefully constructed—one compliment at a time.

Rather than repeat everyone else’s theories, I have one of my own. Where but in the pages of WONDER could I discuss the law of indirection as it applies to these moody little pictures? We know that Lewton didn’t want to make horror movies; but as a natural craftsman, he did his best with the assignment. We know he learned about being a creative producer from the archetypical practitioner, David O. Selznick. We know that Lewton fancied himself as something of a poet. The law of indirection states that better results are often realized if you come at something sideways rather than head-on. Point of interest: this may have been the guiding principle of WONDER’s favorite writer, G. K. Chesterton.

Rather than repeat everyone else’s theories, I have one of my own. Where but in the pages of WONDER could I discuss the law of indirection as it applies to these moody little pictures? We know that Lewton didn’t want to make horror movies; but as a natural craftsman, he did his best with the assignment. We know he learned about being a creative producer from the archetypical practitioner, David O. Selznick. We know that Lewton fancied himself as something of a poet. The law of indirection states that better results are often realized if you come at something sideways rather than head-on. Point of interest: this may have been the guiding principle of WONDER’s favorite writer, G. K. Chesterton.

In the Lewton case, there is more at work here than taking a title like I Walked With a Zombie and making Jane Eyre in the West Indies, while leaving it up to the front office to exaggerate the sensational elements for the ad campaign. For one thing, I Walked With a Zombie is a better story than Jane Eyre.

My theory is that the Val Lewton films are not primarily about fear, or terror, or death or any of the other nice words we use in place of horror. I believe these films are uniquely a product of the World War II era, and that their strongest theme is about what it means to be alone. No other body of films has so touched the center of what it means to be deeply unhappy about the loss of a loved one. These pictures capture the saddest moments in American cinema.

Consider that the first in the series, Cat People, was released in 1942; the last one, Bedlam, in 1946, when the dust had yet to settle over a tortured world. Obsessive concern over personal death receives so much attention in our own craven era that we have forgotten that once upon a time there was a generation more worried about losing a loved one than the thought of individual extinction. This is indeed real fear but of a very different kind than is normally discussed in articles about horror movies. These Lewton pictures counted on the fact that their audience was made up of people who understood how hard it is to find someone to truly love ... and now the future promised them a black pit of uncertainty.

Not one of the Lewton horror films had anything to do with the war. They spoke to an emotional need which was amplified or made immediate by the war, but which Hollywood was largely ignoring in the tidal wave of propaganda being churned out by the studios at the time. In most of these “war effort” pictures personal concerns had no place (an attitude immortalized in Casablanca when Bogart tells Bergman that the love they feel for each other doesn’t amount to a hill of beans in this world—and if you don't remember it that way, gentle reader, listen a little more closely next time). In the Val Lewton horror films, love counts for a lot more than a hill of beans. (Lewton's one film that did deal directly with the war was not a horror picture. It will be discussed in due course).

The personal realm cannot help but touch on the transcendental. For 1940’s movie goers with genuine religious convictions, any entertainment that took them away from the newsreels must have come as a welcome relief. For those without religious faith, there was at least the power of that era’s feelings about romance—an inner state almost equally alien to the contemporary mood. When dealing with supernatural subjects, a great filmmaker could do things on an emotional plane that no special effect can touch. This was because old time Hollywood banked on the link between faith and emotion. In other words, the important thing about a spook was that it could take away our loved one ... or be your loved one. Compared to that, who gave a damn about a body count?

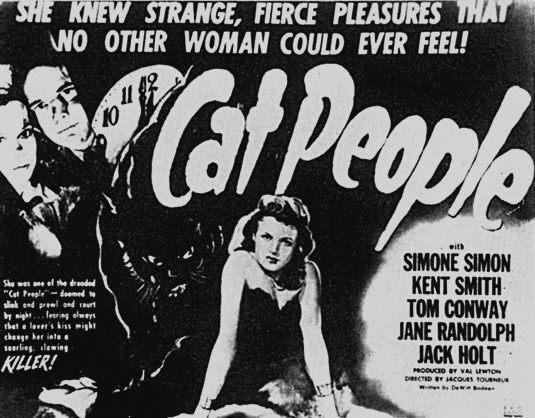

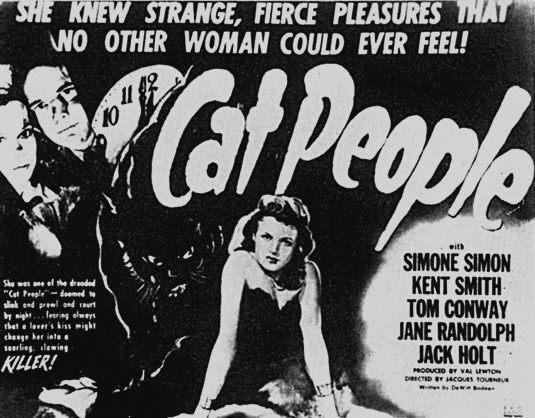

"The picture made Simone Simon into a cult star."

"The picture made Simone Simon into a cult star."

Of course, Theory is empty without Practice. The specific techniques that Lewton’s film perfected are the reason these films will never be forgotten. The most famous Lewton technique is the “bus”—a standard term for a now common bit of filmic indirection. In Cat People, a woman is being stalked by a lycanthrope. It is late at night. Every sound is amplified. She walks faster. Suddenly we hear a hiss. Everything has prepared us for the attack of a panther. The last thing we expect is the hydraulic sound of bus doors opening! So a specific moment in Val Lewton’s very first horror picture is so memorable that it becomes a part of the vocabulary of film.

Influence begets influence. There is nothing surprising in the claim that Hitchcock so admired the shadows cast on a shower curtain in Lewton’s The Seventh Victim that these shadows reached out over time to paint the shower curtains in Psycho an even deeper black. Film is the essential collaborative medium. Before Lewton or Hitchcock, there was Fritz Lang. Creative filmmakers from Orson Welles to Edgar G. Ulmer worked together in a 75-year effort to map out these shadowlands.

Before focusing on each of his films, it must be appreciated that the achievement of Val Lewton lies in the manner in which he applied all the tricks of his trade to produce a cumulative effect that was emotionally right. At least, he never went wrong in a horror movie.

I think it’s also worth pointing out that these techniques operate independently of the moral sense. Although most films that opt for the subtle approach tend to inhabit the moral world view advanced by WONDER, there are notable exceptions. The creative director/producer team of Roman Polanski and William Castle used these techniques to great advantage in Rosemary’s Baby—a picture not generally on the recommended list for the faithful. In contrast, Lewton’s brand of subtlety is left far behind in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, a Grand Guignol pro-Christian splatter film! But having admitted these few exceptions, I am the first to admit that the way of the shadow usually better suits a universe of gods and judgment. Today’s vocabulary of icky details seems to be more a part of the language of the modernist world view.

Having advanced my theory of the Lewton Loneliness Theme, and how this is at the heart of spiritual terror, it seems only right to look for evidence of it in the films themselves ...

Cat People is the most famous Lewton film, released in 1942, directed by Jacques Tourneur. The picture made Simone Simon into a cult star. Years before Hammer used the phrase “French sex kitten”, Lewton was in there pitching. He took this fascinating woman (who had left Hitler’s Europe) and did what great films can always do—make the most of a limited talent. Whereas the 1982 remake is about sex, the original is about longing. Nastassia Kinski (who took the lead in the ‘82 version) is frankly a better actress, but Simone was ideal at projecting a quiet sense of frustration. A very good actor, Kent Smith, had arguably the best role of his career as the hero (some prefer him as Peter Keating in The Fountainhead).

CAT PEOPLE is the most famous Lewton film

CAT PEOPLE is the most famous Lewton film

Along with Simone, another limited performer began a series of fine performances for Lewton. This was Tom Conway (brother of the more famous character player George Sanders) who is perhaps best known to movie buffs as The Falcon. His rather stiff screen persona was usually off-putting but Val Lewton made ideal use of it, casting Conway as a series of sophisticated men who have mastered the art of emotional repression. Of course, normal human repression can hardly compare to what Irena (Simone’s character) must endure. Her curse is such that when her passion is aroused, she becomes a panther that must kill her lover. This has produced some slight strain in her marriage to Kent Smith. So when Conway’s lecherous psychiatrist releases her repressed sexuality, the picture becomes a symphony of shadows, conducted by Conway’s sword cane—but nothing can save his life.

These characters are alone and unhappy, except for the career woman played by Jane Randolph. Her role is to bring the Kent Smith character back to the normal world after his frustrating marriage in-name-only to a werecat. Randolph has her work cut out for her. (In passing, it should be noted that though materialistic explanations for the film’s weird events are continuously offered, by the fadeout everyone has been forced to accept the reality of the supernatural—a makeshift cross has power over the lycanthrope, along with the words “Irena, leave us in peace!” spoken to great effect by Kent Smith.)

I Walked With a Zombie was released in 1943, also directed by Jacques Tourneur. For my money, I Walked With a Zombie contains the most powerful images in any of the Lewton films. The sequence where the nurse and the zombified wife walk to a voodoo ceremony is Lewton visual poetry at its best. The shot of the zombie guardian (the truly impressive Darby Jones) standing like a statue in the twilight of the sugar cane fields as the wind blows away our doubts, is my single favorite moment in these films.

"The shot of the zombie guardian (the truly impressive Darby Jones) standing like a statue in the twilight

"The shot of the zombie guardian (the truly impressive Darby Jones) standing like a statue in the twilight

of the sugar cane fields as the wind blows away our doubts, is my single favorite moment in these films."

Tom Conway is back and perfect in his part, with the best dialogue of the picture, explaining to the nurse coming to work for him (Frances Dee) why the beauty of a Caribbean sea at night is deceiving. He makes sure that she understands how the light she sees in the ocean takes its gleam from millions of tiny dead bodies. It's the glitter of putrescence. “There's no beauty here—only death and decay." Naturally, she falls in love with him right away. Naturally, the relationship is doomed. This scene effectively sets the tone for what is to follow.

Dee is soon faced with the cosmic implications of real zombies in the West Indies. Conway’s wife has been turned into a zombie and now he must care for her. His alcoholic half-brother Wesley (James Ellison) blames him, and we soon learn that Wesley had a romantic attachment for his brother’s now undead wife. A neat touch is that as a nurse, Dee cannot help but keep track of Wesley’s drinking because she can always tell just by looking how much someone has poured of a liquid!

Before moving on, it should be noted that Lewton’s portrayal of blacks was the most realistic and humane of the period. An example is the performance of Teresa Harris as the house servant Alma in Zombie, who has wonderful lines, such as when she awakens Dee in the morning, gently pulling on the nurse’s toe and saying, “I didn’t want to frighten you out of your sleep, Miss. Tha’s why I touched you farthest from your heart.”

There are some admirers of Lewton who try to deny the supernatural aspects of I Walked With a Zombie, as if a serious artistic film (which this obviously is) could not possibly deal with the fantastic (that notoriously juvenile concern). These are the same folks who would insist on a naturalistic explanation for The Turn of the Screw. I believe the best answer to them is found in an article by Ronald V. Borst in that grand old fanzine PHOTON (#17). He writes, concerning Conway’s zombie wife: “Christine Gordon cannot be anything else but a zombie, as there is a scene showing the hungan (Gino Maxeur) passing a sword through her body without effect and, at the climax, she dies just as the hungan stabs her effigy.” Later Borst says that Lewton “wants his audience to seek a logical explanation and gradually wears down their resistance to an acceptance of the supernatural...” The character Mrs. Rand (Edith Barrett) might have a few words for the critics. She represents science and Christianity and Voodoo. She believes in all of them on an island where Christianity and paganism meet.

Likewise, there are critics who try to muster a materialist explanation for Cat People, which is even more absurd! Irena Dubrovna either turns into a great cat, or else everyone else in the story is insane, especially the doctor who dies from ... what? Part of this confusion may stem from the fact that the majority of Lewton’s horror films really aren’t about the supernatural; but his treatment of mood and psychology never varies. So it is that if a character in a later film believes in the supernatural in an instance where the explanation is clearly naturalistic (Isle of the Dead), the emotional impact is the same as in the films where there really are things that go bump in the night. Spiritual terror is inside the head, a place where there is room for consideration of a larger universe than is offered by the contemporary slice-and-dice school.

The very next film is Tourneur’s last for Lewton, and illustrates better than any other Lewton picture how what they did then is better than what is normally done today. The Leopard Man, released in 1943, has not one drop of the supernatural; but it has several drops of onscreen blood. It contains the most vicious killings of any of the films, and all the victims are young girls—one is still a kid in her early teens who is violently killed by an escaped leopard. The human killer at work turns out to be a psychopath with sexual problems. If this sounds like a recipe for one of today’s slasher films, the point is how a Lewton production treated this material to once again show us the inner landscape of the mind instead of wallowing in an exterior landscape of spilled entrails.

The first two films had original screenplays. The Leopard Man was based on a novel by Cornell Woolrich, most famous in movieland for Hitchcock’s version of Rear Window. For lovers of the noir style in suspense fiction, Woolrich is a seminal figure. The perfect appreciation of this film was written by another seminal figure in the related genre of dark urban fantasy, Harlan Ellison. Writing in the 1966 issue of CINEMA, in his article “3 Faces of Fear” (reprinted in Over The Edge, Belmont Books), Ellison describes The Leopard Man’s most famous scene as follows:

“Mommy! Open the door!”

“Mommy! Open the door!”

“Mommy, open the door the leopard is after me! The mother's face assumes the ages-old expression of harassed parenthood. Hands on hips, she turns to the door, you're always lying, telling fibs, making up stories, how many times have I told you lying will—

“Mommy! Open the door!”

“You'll stay out there till you learn to stop lying!”—

“Mommy! Mom—

“Something gigantic hits the door with a crash. The door bows inward and dust from between the cracks sifts into the room. The mother’s eyes grow huge, she stares at the door. A thick black stream, moving very slowly, seeps under the door.

“Madness crawls up behind our eyes, the mother’s eyes, and we sink into a pit of blind emptiness ....”

As Ellison makes clear, the blood is the exclamation point at the end of a brilliantly wrought passage. The blood is only there because there is no other way to make the point. He goes on to say how that image has stayed with him all his life.

Joel Siegel’s book claims that Lewton and Tourneur later disowned the film, but I hope this isn’t true. They should have felt no more guilt for how this material can be mishandled than Alfred Hitchcock or Robert Bloch should have felt for the progeny of Psycho. No subject matter is immune from bad taste; and good taste can transform anything into a meal fit for a gourmet.

The emotionally repressed figure in The Leopard Man is played by James Bell, who was good as doctor and professor types for Lewton (he was the family physician in I Walked With a Zombie; here he plays the curator of a museum). The quiet, almost hands-off manner in which he admits how he killed two women, and made it look like the leopard’s doing, is terrifying because the motive is so odd. He’d originally intended to save the girl trapped in the cemetery, but her fear reached him in a way he’d never experienced before. Basically, he kills to experience human contact; to escape his loneliness for a moment.

There are no supernatural forces at work here (unless one wishes to argue that all murderers are possessed). But the scene of monks dressed in black hoods, marching in procession to do penance for centuries-old murders as the boyfriend of one of the murdered girls guns down her killer ... man, if this doesn’t touch the heart of spiritual terror, I don't know what does!

"There are no supernatural forces at work here..."

"There are no supernatural forces at work here..."

The Seventh Victim, also released in 1943, addresses spiritual concerns in an unambiguous manner. Directed by Mark Robson (who had been Lewton's film editor on Cat People) this was Hollywood's first serious treatment of Satanism since Ulmer's The Black Cat (1934) (and depending on how camp one finds that classic Karloff/Lugosi vehicle, the Lewton picture might count as the first serious treatment, period). This story doesn't actually seem to require the existence of the supernatural; belief in the devil (even if he only lives in our hearts) is what matters here.

The theme of loneliness and alienation is so intense in The Seventh Victim that some Lewton fans find this one a bit too much. It was a commercial failure. Not too surprising I suppose, for a film in which the pain of being alone is so terrible that suicide is a welcome option for more than one character. Joel Siegel writes, “Lewton was a man haunted at times by his own demons, and The Seventh Victim allows free expression to this morbidly romantic side of his nature.”

Kim Hunter plays an orphan who leaves a joyless school for young women to go to joyless New York in search of her sister, Jacqueline (Jean Brooks) who has fallen in with Satanists. There she meets our old friend Tom Conway, playing a psychiatrist again! He leads the younger sister to the older.

The doctor has been unable to cure Jacqueline of her desire for death. It is only when the diabolists, who call themselves Palladists, insist on Jacqueline’s death for an infraction of their rules that she balks. She wants to be the one to decide. When we see the Palladists trying to force her to drink a glass of poisoned wine we cannot forget her rented room where we have seen that she keeps one chair and a hangman’s noose.

"...we cannot forget her rented room..."

"...we cannot forget her rented room..."These Satanists are bored socialites. Their most interesting member is a one-armed woman who has joined the devil’s party because of the injury life has done her. In the most frankly religious scene (often disparaged by fans) the Palladists are temporarily shamed by the reciting of the Lord’s Prayer. The moment is exquisite. Other exquisite moments abound; a procession of forlorn faces at the Missing Persons Bureau, Hugh Beaumont’s failed poet, Jacqueline being chased at night, and the really surprising death of a private investigator.

One particular exchange of dialogue sums up this most personal of Lewton’s films. A character observes that one of the Palladists struck her as “sort of lonely and unhappy”. Another answers, “I guess most people are...”

Next we turn to the least seen of these films, The Ghost Ship (another 1943 release!) also directed by Mark Robson. Recently, the film has become available again. The story is a familiar one, the most famous example courtesy of Jack London (The Sea Wolf). The idea of a crazy captain who is a menace to his crew might strike the average sailor as fit subject matter for a documentary (Melville’s Moby Dick would qualify except that Ahab’s mania is focused on the whale instead of the crew; and many of the crew are caught up in their captain’s obsession).

Captain Stone is played by Richard Dix. He is a sympathetic villain (as Karloff’s will be in Bedlam). In his horror films, Lewton insists on showing the human side of his villains; but this does not prevent the heroes from being truly heroic. A typical modern error is to assume that you have to make your heroes completely good and your villains completely bad (a thoroughly un-Christian notion) or else sink into the mire where there is no good or evil and everyone is nasty. Lewton knew better.

Russell Wade is the hero. He doesn’t want to believe that the captain is nuts but finally he can’t deny that the commanding officer is murdering his crewmen... just a few now and then. The sailors do not realize what is happening, and when the Wade character tries to save them they become convinced that he is the one who is the nut. Lewton makes effective use of inanimate objects, turning the ship itself into a kind of monster worthy of a scene out of a William Hope Hodgson story. Terror is to be found in everything from a heavy iron hook to the anchor chain.

In the end, it comes down to a problem of dealing with one man who takes his life-and-death authority over his men a bit too seriously. Siegel writes, “One could take The Ghost Ship’s ambivalent attitude over authority... as some sign of Lewton’s own complex feelings about the dangers and powers of being a movie producer.”

"He doesn’t want to believe that the captain is nuts..."

"He doesn’t want to believe that the captain is nuts..."

By this point, the success of Cat People (the modest little B-movie had become the sleeper hit of 1942) led to the inevitable. RKO wanted a sequel. Lewton did not see eye to eye on this with the front office—he’d said everything he wanted to say on this subject. RKO had a simple position, too—no subject was closed where the box office was concerned. So they assigned the producer the title The Curse of the Cat People and told him to get to work. Lewton took that obvious and thoroughly unoriginal title and made a film that almost defies description. Almost.

The picture was released in 1944. The three principals were back—Simone Simon, Kent Smith and Jane Randolph reprising their roles from the original, Irena, Oliver and Alice. And there any resemblance to Cat People ends. The directors were Gunther von Fritsch and a man who would go on to one of the great careers in movies, Robert Wise.

The story of Curse of the Cat People is so much in the spirit of WONDER that I wonder how Rod and Lint found a time machine and managed to get back to the days of yesteryear to write the script attributed to DeWitt Bodeen (Siegel says that despite the Bodeen credit, the script was largely Lewton’s.) Along with a special handful of films Invaders from Mars, The 5,000 fingers of Dr. T, Phantasm and The Invisible Boy—Curse of the Cat People is entirely focused on a child’s imagination and how what happens is filtered through that imagination. We're in Ray Bradbury country.

Right off, it should be said that it doesn’t matter a fig whether the ghost of Irena is actually showing up or if it’s all a projection of the lonely child’s mind. The fundamentals of the story work either way (battles with RKO left their scratch marks on the production and there are clues which point in both directions, re: the supernatural.) Ann Carter is excellent as the little girl, Amy. Her father, the Kent Smith character, is scared to death of her imagination. One can almost sympathize with him considering what he went through in the first film... but that doesn't compare with how we feel about the little girl.

Irena appears as Amy’s friend. Simone’s performance is sweet and haunting. I prefer this of all her roles, even better than her chilling portrayal of a demonic succubus in the classic All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil and Daniel Webster). She wins over little Amy—and us. The main story concerns Daddy’s efforts to cure Amy of the delusion that she has been seeing and conversing with the dead Irena. Certain psychological theories of the day were especially hard on imaginary friends. But there's also a great subplot; Amy begins spending time with an old lady, a grandmother archetype right out of a fairy tale. Julia Dean plays the part with great gusto. All is not well in this household either. The old lady denies that her daughter is her daughter. (Elizabeth Russell plays the embittered daughter—we saw her previously as the only other cat person in the original Cat People. She also does a nice bit as a dying woman in The Seventh Victim.) The daughter hates Amy for winning her mother’s affection.

The ultimate WONDER scene has got to be when the old lady entertains Amy by telling the child the story of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. This scares Amy good and proper! Later, when the little girl faces real danger, she remembers the Washington Irving story. More importantly, her faith in Irena, the good ghost, saves her in a manner both surprising and touching. I'll say no more, except to repeat that in this story the reality of Irena is less important than the child’s belief in Irena as a benevolent spirit.

"Irena appears as Amy’s friend."

"Irena appears as Amy’s friend."

The foregoing Lewton films were set in contemporary times. Before turning to his last three horror productions, all period pieces with better budgets and bigger casts, I should say a few words about the superlatives that keep appearing in this article: “best” and “perfect” and “favorite”. I plead reality. This handful of films achieved remarkable things. If Lewton’s fame rested only on what has come to this point, it would still be a sturdy fame indeed. No Lewton picture ever had better photography than I Walked With a Zombie. None ever had a moment of greater terror than The Leopard Man. But for my money, the best was yet to come.

For as long as I can remember, Boris Karloff has been my favorite actor. Not favorite horror actor, mind you, but favorite actor. I freely admit that I love all actors and actresses associated with the horror movies. I've never seen a character actor I didn’t like; but something about Karloff spoke to me from the start.

Karloff thought Lewton gave him the best movie roles of his career. There is some competition for this honor. Karloff never downplayed his debt to James Whale and the opportunity that fine director gave to a minor character actor who was no longer young. Toward the end of his life, Karloff would be given a magnificent part by Peter Bogdanovich. There are some who vote for Karl Freund as the man who gave Karloff the role of a lifetime, but I agree with Karloff that the three pictures he made for Val Lewton are the peak, the films that brought this polished, poetic horror series to a triumphant climax.

The three Karloff films work together so well that a few more comments are in order about them as a body of work. Lewton’s visual imagination has often been praised to the exclusion of other virtues. This was a man who knew light and shadow, knew symbol and allusion ... a man who had the gift of all great filmmakers and found directors of like mind. These guys filled the background picture with such a wealth of detail that repeated viewings are simply a must.

The trouble is that some of the critics who love the visual side of Lewton lack the, shall we say, education to appreciate the literary side of his mind... precisely the part of his imagination that comes to full flower in the Karloff films and makes explicit what had often remained implicit in the earlier work. One might say that Lewton’s Russian soul was a literary one, and that he realized how the advent of sound in movies had created the possibility of T-A-L-K-I-N-G pictures. The Karloff trio is just as cinematic as it is theatrical.

At least the critical consensus has come to agree with Boris Karloff about the value of his performance in the first of these—my choice for the best role of Karloff’s career—the title character of The Body Snatcher. This performance is so remarkable that it has become the cornerstone of an ongoing reappraisal of Karloff’s abilities as an actor; critic Danny Peary, author of Alternative Oscars, even takes away Ray Milland’s 1945 Lost Weekend Best Actor Award and gives it to Boris Karloff! We fans, of course, never doubted his grand talent for a moment—we who have seen him give subtle, shaded portraits in even the cheapest three-in-the-morning poverty row quickie—but to finally see him widely acknowledged by mainstream critics is very gratifying. His other two Lewton performances are nearly equal to Body Snatcher. The Isle of the Dead makes ideal use of Karloff’s uncanny ability to seem menacing and vulnerable at the same time; and the final picture, Bedlam, is such an intelligent film, with such an intelligent performance by Karloff, that it is a miracle such a product could issue forth from Hollywood.

"...my choice for the best role of Karloff’s career..."

"...my choice for the best role of Karloff’s career..."

The Body Snatcher was released in 1945, directed solo by Robert Wise who would later direct The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Haunting and other triumphs. Based on the Robert Louis Stevenson story, the film is also important as the last time Karloff was to work with Bela Lugosi; the moment when Karloff “Burkes” Lugosi is nothing short of magnificent. As long as the superlatives are flowing, due honors must be paid to Henry Daniell for the best performance of his career, as well. A solid character actor, he is also remembered as one of the comic Nazis in Chaplin’s The Great Dictator.

The nineteenth century details are what one would expect from Val Lewton (1831 Edinburgh to be exact). Russell Wade is a medical student who is initiated into the higher mysteries of the art by Dr. Wolfe MacFarlane (Henry Daniell) who runs a medical school and deals with “the redoubtable Gray” (Boris Karloff, a cabman with a profitable sideline of stealing corpses from the local graveyards). The young student learns that the respectable surgeon and the disreputable body snatcher have known each other for a long time, and each had some connection with the famous “Burke and Hare” case. Gray derives great satisfaction from holding the past over MacFarlane’s head. For his part, MacFarlane wants to be rid of Gray but needs the bodies that his enemy provides.

The Body Snatcher is about ambivalence. MacFarlane is a divided character, a brilliant intellect but cold and distant from his patients, a man who thinks he wants to be free of everything Gray represents—but who actually knows less about his inner self than Gray knows. A remarkable moment comes at the local tavern when Gray explains that MacFarlane’s face shows the knowledge he has obtained over the years but that this is knowledge of death, not life.

Ambivalence touches the heart of the young medical student when he intervenes on behalf of a young girl who needs an operation that only MacFarlane can perform. Without realizing what he does, the student sets into motion a series of events in which Gray kills a woman to provide a crucial spinal section without which MacFarlane cannot perform the study he must do before operating on the girl. This, in turn, sets other wheels of the plot turning, and in the end MacFarlane finds out that he cannot be rid of Gray ever, ever, ever. The climax is another Lewton moment where psychology can probably explain everything, but there is the slight possibility that the supernatural has revealed itself again, this time in the glowing cadaverous form of Karloff-risen-from-the-grave. He's a hard man to kill in the movies.

Isle of the Dead was also released in 1945, directed by Mark Robson. There is no question of the supernatural here. The characters who believe in vampires are dead wrong (pun intended). Much of the horror derives from this false belief. And yet the twin themes of loneliness and spiritual terror are evident in every frame, a film that virtually reeks of death. There is a pale, washed out quality to the pictures, as if life itself is draining from the screen. Of all Lewton productions, this is the one that owes the most to Carl Dreyer, who explained to his crew when making Vampyr (1932) that the feeling he wanted throughout the film was of a person sitting alone in a room and then being informed that just beyond the door is a corpse. You never see the corpse. But the knowledge that death is next door alters how you see the light and shadows.

The place is a Greek island during the 1912 war during an outbreak of the plague. Karloff plays a Greek general who is responsible for quarantining a group of people so that the disease will not spread to his troops. They take what precautions are possible as outlined by the doctor (Ernst Dorian), but one by one they begin to fall victim to the plague. As the disease spreads, characters with religious leanings rediscover faith. The character played by Jason Robards Sr., makes a sacrifice to Hermes, and we are not sure how much of this is to be taken seriously and how much is an ironic jest. The general champions the materialistic view as long as he can, especially scornful of an old peasant woman (Helene Thimig) and her belief in the “vorovalka”, a local version of the vampire myth. It is only when the general succumbs to the illness himself that the old folklore seizes his mind and he becomes a threat to heroine Ellen Drew, who he becomes convinced is a vampire.

"Karloff plays a Greek general..."

"Karloff plays a Greek general..."

The Ellen Drew character is companion to Mrs. St. Aubyn (Katherine Emery), who is suffering from health problems predating the plague: the Edgar Allan Poe disease, catalepsy! The old peasant woman sees the healthy face of Ellen Drew (who doesn't succumb to the plague), the wan face of Mrs. St. Aubyn, growing weaker and weaker—and draws a perfectly logical conclusion... that just happens to be wrong. After she plants the seed of superstition in Karloff’s general and Mrs. St. Aubyn is prematurely interred, we get ourselves a proper horror film.

The last Val Lewton horror film is Bedlam, released in 1946 and directed by Mark Robson. The film was banned in England for decades, not because of the horror content but for political reasons. (American fans often forget that no other country in the world has anything close to the First Amendment). With his love of costume, architecture, furniture and all the little details of place and time, Lewton had a field day recreating the eighteenth century. An indifferent filmmaker running a B-unit at a big studio would simply raid the wardrobe department and take whatever he could find. In contrast, Lewton knew history. Bedlam is as fine a re-creation of its period as ever came out of Hollywood.

As long as the superlatives are flowing again, Anna Lee (who had worked with Karloff in England) turns in the finest female performance in any of these films. More than that, I nominate her performance here as the best by an actress in any horror film! When I first saw this film as a kid, I fell in love with her.

There are people who watch this movie all the way through and can’t understand why it was considered a horror film. And yet it has a premature burial, torture sequences, someone who smothers to death after being completely covered with gold paint (long before James Bond discovered how Auric Goldfinger disposed of old girlfriends) and one of the great terror situations, a sane person imprisoned among the mad. Bedlam influenced many later horror films with its definitive portrayal of an old-fashioned madhouse.

"Karloff plays Master Sims..."

"Karloff plays Master Sims..."

Karloff plays Master Sims, the Apothecary General of Bedlam. He is an intelligent man who has fought his way up from the lower classes to become educated and cultivated. His resentment of the aristocracy runs deep. The funniest line in the film comes when he refers to the saner members of Bedlam as the aristocracy of the place, proving a law of physics—namely that scum, like the lighter elements, always rises to the top. When he gives in to his sadistic impulses he derives no real pleasure from what he does. Every day, in every way, he tries to convince himself that his view of life is correct and that what he does is justified.

Anna Lee’s Nell Bowen has come up the hard way as well, to become the companion of Lord Mortimer—a brilliant caricature of a Tory buffoon courtesy of Billy House. An intellectual war is fought between Sims and Nell over Mortimer, whose money and power can make a great difference to the conditions in Bedlam. At first Nell would just as soon avoid “ugly things in a pretty world”, but a Quaker (Richard Fraser) starts her to wondering—always a dangerous occupation for those who have found their small measure of contentment in the world.

"I wish I could end this article here..."

"I wish I could end this article here..."The battle of wills finally places Nell in the hands of Sims; she has been committed to Bedlam on a flimsy pretense (her own wit and sense of fun turned against her at a sanity hearing). Fortunately she has made friends with a prominent Whig before she falls into the Karloffian trap and the Quaker will not rest while she is imprisoned. The climax is unforgettable as Sims is put on trial by the loonies... and one of the loonies was a lawyer! Rarely has there been a more chilling portrayal of justice, or a more eloquent speech than Karloff’s as he explains how he has been frightened and alone all his life. His speech is a reminder of an earlier comment when Anna Lee first sees the poor souls in Bedlam and say,: “They're all so lonely. They’re in themselves and by themselves.”

Bedlam ends with Nell’s conversion to Christianity, of the Quaker variety. The conversion is combined with her love for the Quaker who has helped to save her in such a manner that many viewers might miss it altogether. But the religious subtext is there; a perfect ending for the only movie ever inspired by a William Hogarth painting. There would be no more Val Lewton horror films.

I wish I could end this article here, but I made a promise earlier to discuss the one Lewton film which dealt in a direct way with war—the subject which I have maintained was the indirect inspiration for them all. Although a period picture set at the time of the Franco-Prussian War, the parallels to ongoing World War II are unavoidable. I'd heard about Mademoiselle Fifi for years but could never track it down. When it finally ran on late night TV, I eagerly awaited the moment. Perhaps this was another unheralded B-movie masterpiece from the man who was perhaps Hollywood’s greatest practitioner of the art of making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

There are plenty of World War II movies I enjoy that were made during the period of hostilities. I like all of Fritz Lang’s contributions (especially Ministry of Fear). I like all of Alfred Hitchcock’s (especially Lifeboat). I admire John Ford’s They Were Expendable. I assumed that Lewton would bring the same taste and intelligence to Mademoiselle Fifi that had enriched his other productions. He just had to be in that select company of filmmakers who would not falsify emotion or give in to cheap hysteria just because World War II was raging. Hey, we’re talking Val Lewton here.

The picture, directed by Robert Wise, was released in 1944. For the first half of the film I thought I was safe in my optimism. The script was based on two stories by Guy de Maupassant. Reliable members of the Lewton repertoire company were back, i.e., Simone Simon and Alan Napier from Cat People and Jason Robards Sr., from Isle of the Dead.

Given the production code of the period, I knew full well that there would be changes in the de Maupassant original. A story about a prostitute who saves a bunch of snooty prigs and snobs who repay her with resentment was not going to make it (no pun intended). I didn’t mind that they changed Fifi into a laundress. I didn’t mind that attempts by the Prussian officer to force his attentions on her didn’t work out the way they would have in reality. All this I could forgive. Lewton could work with this material, touch the emotions and get across his special kind of mood.

Here’s what I did mind: Simone Simon with rifle in hand, blazing away, killing her quota of caricature Germans at the climax. I mean, she’s out there like John Wayne outnumbered, but blasting her way into the pages of history. There are actresses who might have been believable in this scene. Simone Simon is not one of them.

"I didn’t mind that attempts by the Prussian officer to force his

"I didn’t mind that attempts by the Prussian officer to force his

attentions on her didn’t work out the way they would have in reality."

Shot down is poor old Guy de Maupassant for writing such an unpatriotic story as to suggest that the French middle class could be hypocritical. The political mauling of his work puts one in mind of the sort of thing that went on in the Third Reich. If we could bring back the ghost of de Maupassant, I have little doubt how he would respond to this travesty. He’d turn the Horla loose on Hollywood! (In case you don't know the Horla, it’s one of the best horror stories ever written and was adapted for radio with a brilliant performance by Peter Lorre.)

I wouldn’t mind this movie coming from some Hollywood hack, but from Lewton the experience is painful. No room for soul searching here. And the cure for loneliness is to pick up a gun and do your part for the war effort.

This is not to fault Val Lewton for doing his part regarding the war effort, but a few creative individuals made patriotic movies without compromising their artistic standards. I mentioned before how much I liked Lifeboat, made by Lewton’s friend Alfred Hitchcock. It is one of the most effective anti-Nazi pieces made during the war. And yet, because Hitchcock stayed true to what he knew of human character—refusing to pander to all the homegrown Dr. Goebbels types in New York and Hollywood insisting on caricatures—some critics (predictably) accused Hitchcock of being soft on the Nazis! This was especially humorous as Hitchcock went home to England for a while during the war, putting himself at risk, to make films aiding the war effort. Collectors can now have the dramatic featurettes he did about the French Underground. How many of his critics put themselves at risk? Frankly, all of Hitchcock's films, all of Hitchcock’s anti-Nazi films live up to this high standard. Even Goebbels himself admired Foreign Correspondent.

The reason I fault Mademoiselle Fifi as the only lamentable Lewton production is not because of the patriotic stuff but because he forgets to be Val Lewton. His other non-horror films, Youth Runs Wild (1944), My Own True Love (1948), Please Believe Me (1950) and Apache Drums (1951) do not compare to his macabre work, but he doesn’t forget to be Val Lewton. The significance of Fifi is obvious: by virtue of what it is not, we can appreciate his horror films all the more.

One more thing: the gray areas where live the monsters and villains in Lewton’s horror films ring that much more true-to-life when contrasted with the complete lack of such shadings in Fifi. True spiritual terror must take into account that here in the real world mere mortals are never simply “good guys” or “bad guys”. As C.S. Lewis often pointed out, no mere human being can achieve the purity of absolute evil—for that we must look to malevolent spirits. No, spiritual terror is fearing the villain... and then realizing that he might just be us.

To conclude this rather personal appreciation of a rather personal movie-maker, those of us who care about values must remember that in our efforts to champion good taste and a high view of humanity in films, we must not rely on mere nostalgia. There never really was an Edenic period in Hollywood history; the careless destruction of subtlety and nuance has always been the norm in Tinseltown, not the exception. But Val Lewton is at least one proof that Hollywood used to have better instincts about the feelings of real people.

War fever did as much to make the audience stop thinking in its day as the splatter punk nonsense and crime orgies do for audiences today. The Lewton horror films are a shining exception, a monument to humanity. For those who say the horror film can be a deadly trap for a gifted filmmaker, I argue the opposite. For Val Lewton, the horror film offered artistic freedom. Those who have known the pain of loss should be forever grateful.

|

Rather than repeat everyone else’s theories, I have one of my own. Where but in the pages of WONDER could I discuss the law of indirection as it applies to these moody little pictures? We know that Lewton didn’t want to make horror movies; but as a natural craftsman, he did his best with the assignment. We know he learned about being a creative producer from the archetypical practitioner, David O. Selznick. We know that Lewton fancied himself as something of a poet. The law of indirection states that better results are often realized if you come at something sideways rather than head-on. Point of interest: this may have been the guiding principle of WONDER’s favorite writer, G. K. Chesterton.

Rather than repeat everyone else’s theories, I have one of my own. Where but in the pages of WONDER could I discuss the law of indirection as it applies to these moody little pictures? We know that Lewton didn’t want to make horror movies; but as a natural craftsman, he did his best with the assignment. We know he learned about being a creative producer from the archetypical practitioner, David O. Selznick. We know that Lewton fancied himself as something of a poet. The law of indirection states that better results are often realized if you come at something sideways rather than head-on. Point of interest: this may have been the guiding principle of WONDER’s favorite writer, G. K. Chesterton.