|

|||||||||||||||||

November 2009 Web Edition Issue #3 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Mondo Cult

Forum

Blog

News

Mondo Girl

Letters

Photo Galleries

Archives

Back Issues

Books

Contact Us

Features

Film

Index

Interviews

Legal

Links

Music

Staff

|

I come to puree Patterson, not to braise him. Bill was the antiparticle to his magnum opiate: He was never "in dialog with his century." He belonged to an altogether different universe, a being of pure intellect. A theoretical thetan, but a practical pratfall. Bill was a reservoir of all knowledge, but was unable to apply any of it upon demand. He was a classic absent-minded professor, except for not being absent minded. Or being a professor. But you get my drift.

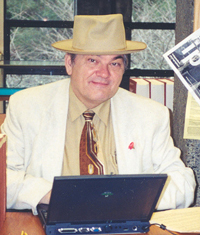

Bill Patterson He was the Impractical Man... except, of course, for the one great thing he did manage to bully into existence: the first proper biography of the universally acknowledged master of science fiction, Robert A. Heinlein. I leave it to others to expound upon Bill's tome, 1,293 pages of pure pedantry and multitudinous minutiae (longer than Moby Dick!). But, as that is precisely what a biography comprises, we can have no complaint. Well, maybe excessive eyestrain. This article ain't about Bill the Author, but Bill the Character. He could have stepped out of a Dickens novel; or more appropriately, one of Isaac Asimov's Wendell Urth stories. Bill was born to be an English epicure. Unfortunately, he was spawned in the decline of the American hodge-podge. Food was one of his passions. I believe he had memorized every cookbook in the Dewey Decimal system, a culinary legend in his own mind. But the first time he actually cooked for my wife and me, he served up a dish unique in the annals of cookery: Shrimp a la Tiretread, microscopic crustaceans, perhaps krill, boiled into lumps of rubber. Once swallowed whole (chewing was an impossibility), they bounced right back up again. We realized that Bill's gourmet talents were entirely theoretical, and any resemblance to actual edibles was purely accidental. There was no second meal; thenceforth, when prandial parties loomed, we did the cooking and let Bill take care of the judgments. But oh, those judgments! Bill was always intensely concerned with tradition and propriety, that the food be prepared properly, without regard to the minor distraction of "taste." As long as every "t" was dotted and every "i" crossed, Mr. Bill was satisfied. Bill's first book, the Little Fandom That Could (this one a mercifully brief 700 pages and self-published), was a didactic, interminable, elegiac, apocalyptic apologia, arguing that that the 1978 World Science Fiction Convention (a.k.a. IguanaCon II)—which Bill Patterson and cohort Tim Kyger accidentally ran, in Phoenix, of all places—was in fact one of the best WorldCons evah, despite it falling to pieces. The event featured (a) a ceramic spittoon of some sort, which contrived to be shot, or exploded, or hurled, or perhaps dropped from a great height—varying by witnesses as in Rashomon—thus destroying the item (on that alone everyone agreed); (b) an imaginary European guest of honor who did not show, could not be proven to exist, and was subsequently erased from the memory pool; (c) Harlan Ellison being roasted in a Winnebago or some such (dayanu); and (d) the WorldCon's first visit from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. A good time was likely had by all. I wasn't there. Bill's first publication already displayed his trademark dissection of every incident down to the cellular level, losing whatever point he was trying to make, yet somehow inducing the reader to continue in horrified fascination, like observing open-heart surgery through an electron microscope. It is the Mount Everest of molehills. I have no clue how Bill could faithfully reproduce (or recreate) so many conversations, confrontations, and consternations; either he had a phonographic and monochromatic memory, or the FBI bumped into Bill at the WorldCon, wiretapped him, then sent him a handy transcript for his memoirs. But the past is prologue; I didn't even meet Bill until three years later, in San Francisco. He always considered that to be his home town; which was odd, since he rarely had the resources actually to live there. Mostly he lived down south (i.e., Los Angeles), and pined. But I'm getting, as usual, ahead of myself. Bill at Bubba Gumps during the Denvention in 2008. PHOTO | Deb Houdek Rule (with permission) Bill belonged to an earlier century, even an earlier millennium; and that's just when I met him, in 1981, while I was attending UC Santa Cruz and playing Discordian Druid. I'd met Tim Kyger (the actual chairman of IguanaCon) through a mutual female hottie, though neither of us got much of that action. On a whim, Kyger (nobody calls him "Tim") and Jim Harding were driving from Santa Cruz to "the City", San Fran. To Bill, "the City", awe-quotes and all, always meant San Francisco; for him, there was no other city, just way stations in between glimpses of paradise. Kyger was organizing the remnants of the L-5 Society (space fandom, more or less) into SpacePAC, the space political action committee, a wonderful organization—during Republican administrations. When the other guys were in charge, SpacePAC had all the clout and prestige of John Kerry at a Christmas-in-Cambodia reunion. Kyger was deadly serious about SpacePAC; in his afterlife, he finagled his way into becoming legislative aides on space and technology, both in House and Senate. I don't recollect Bill Patterson actually attending the SpacePAC meeting itself (he was never much of a joiner, just an enjoyer); but Kyger certainly would never visit the City without spending time with his high-school friend, Bill. On my ride-along, I confess I pegged Bill as a typical fan: tall, fat, acerbic, cranky, nit-picky. But the pose masked a powerful intellect—and also masked a man frantically spinning more plates than he could chew. As usual with Bill, "visit" meant "eating." He led the way to a local pizza parlor, where he ravaged the wagon-wheel sized pizza, nearly devouring the tablecloth in the rush. He reached, reached for the last piece outstanding—then manfully retracted his hand. "Come," he urged, "there's a wonderful patisserie a block down Columbus!" As it happens, I'm deathly allergic to eggs, which tends to diminish my delight in consuming pastries of unknown provenance. So I took the last piece of pizza instead, and followed Bill, Jim, and Kyger out the door. At the sweetshop, I abjured. Our guide took notice; I had to say something, so as not to offend. But I didn't want to go into my medical issues with a perfect (well, practically perfect) stranger. So I said I'd eaten too much pizza to leave any room for a pastry. Bill took on a smug smile, rose to his full height (alarming, even while seated), and announced, "well I am not too full, because I stopped myself!" I thought it was the most pompous utterance I'd ever heard in my then brief life. In later years, when I reminded him of this foible, Bill tried to put it over that he wasn't pompous, just pleased that he'd been able to think ahead and resist the temptation to wolf down the final slice of pizza, which would have diminished even his capacity for a second torte. But I wasn't fooled: Bill's pomposity was one of his finer traits. I saw that same cram-it-all-in struggle in his writings, from the Little Fandom That Could (his first and weakest writing) all the way to the Heinlein biography, his last and greatest. Bill was a completist, which meant including every last tot and jittle his copious research revealed, trivia vying with vital information for space in the writing. Most authors overwrite, then pare back. Bill was the only writer I've known whose every later draft expanded the manuscripts by orders of magnitude. But I reiterate: His prolixity and pomposity were the perfect preludes to the biography. Only a Bill Patterson could have been large enough and contained sufficient multitudes to encompass Heinlein in all his glory (and vainglory). In between the Little Fandom and the Heinlein hegemony, Bill acquired hundreds of follies, effusions, and enthusiasms, which would leap like Athena, fully formed from Bill's brow, stagger through a few months or years, then be relegated to a back burner that was stacked higher than his own head (a lofty tor indeed). For some time, he published Quodlibet, a stuffy, personal fanzine of fabulous pronouncements, from cookery (the only proper temperature to cook a hamburger is evidently well done to the point of overdone) to the angle of Bill's splay-footed stance. He cultivated the useful habit of responding to letters to the editor (himself) directly after the reader's complaint, which vastly facilitated Bill in winning the argument. Then his love of Heinlein pushed Quodlibet aside in favor of the Heinlein Journal. There he initiated a periodical forum on a series of predictions by Robert A. Heinlein about the year 2000, prophecies first enunciated in 1950 and published as "Where To?;" then revisited fifteen years later, and finally reevaluated in 1980. Bill had noticed that the next fifteen-year interlude was fast approaching; so he roped in a number of thinkers, tinkers, and stinkers to render final judgment upon the Great Man, under the guise of "Are We There Yet?" God only knows how many tens of thousands of words I wasted on that unpaid but obsessive perscrutation. Then again, time well wasted. Along the way, Bill was caught up and carried away with natural-language computer programming, a breakthrough that has eluded cyberneticists to this day. I'm not sure what he was thinking, other than that he was good with spelling and grammar. I don't know whether he even had a computer in his house. If so, I visualize a Trash-80 running BASIC in white-on-black. Still, he was utterly convinced he would be the one to crack the natural-language code. It went the way of the boiled shrimps. But I think this was the occasion of my favorite of his casual profundities: I mentioned something about being in the computer age, and Bill mused, as if talking either to himself or his god (assuming there is a distinction between them). "We're not yet in the computer age; we won't be until computers become invisible." Another seminal Patterson project that never matured to fruition was a book that would explicate the origin of every single street name in the City—where it came from, what was the significance, and where were the closest pastry shops. (He could've skipped the street references and leapt straight to the patisseries.) One project left unfinished was not Bill's fault, but mine. After my debut fantasy novel Heroing, which made about as much impact on literature as a speck of lint fluttering from the Burj Khalifa, I flung myself into a real science-fiction novel, the Pandora Point. It was to be my second novel, but things went a little awry; I had unquestionably bitten off more than my head. I skip a couple of decades; I had hither and yon picked at Pandora all along, in between publishing seventeen other books. Still I kept returning to my unfinished manuscript... but always starting in different parts of the novel. Naturally, I realized Pandora had become a higgledy-piggledy mess. On an inspiration, I sent the whole wad of awfulness to Bill Patterson for a critique, which would guide me through my first (and only!) rewrite from start to nuts. A couple of months passed, during which I completely forgot I'd e-mailed Bill. Then came doomsday—the day the novel stood stillborn. Bill had responded by a painstaking destruction of virtually every aspect of Pandora. He tore the major characters to pieces, shredded the plot, torched the setting, and fired the ashes in the general direction of Mount Vesuvius. He stomped on my invented diction and tweezered my multiple personae perspectives. For a small service charge, Bill politely offered to bury the manuscript in a shallow grave. Then he summed up: "In general, Dafydd, you're on the right track. Keep up the good work!" When I was released from the mental ward, I took a longer look at Bill's actual critique. He had included a series of fixes, which were complete nonsense; they would have turned the Pandora Point into an inferior edition of the Little Fandom That Could. But his observations were dead on. I knew I had a mess; Bill's critique finally codified just how much of one! I threw away all of his suggestions and just focused on the problems; as I found my own solutions, Pandora gradually morphed into what I'd imagined so many years back, at a time I couldn't possibly have pulled it off. I'm satisfied that it will be published as my nineteenth; but it would never have seen the light of day without Bill Patterson's acerbic and jaundiced eye. Alas, my greatest regret is that he died before seeing how I resolved the inanities he so gleefully pointed out. (Besides, now I have no cheap editor.)

Bill accepting Robert A. Heinlein's 1951 Retro-Hugo for Farmer In the Sky. There are your information hoarders (say 65% of the human race) and your information distributers (the other 35%); Bill was an information lobber. My wife and I put on a thinkfest party we call "Thanksmas," because it was originally set between Thanksgiving and Christmas, though in these decadent times the movable feast has migrated into January. When Bill began to attend, initially uncertain what to expect (and why he'd come in the first place), he would seat himself on the most comfortable chair and say nothing for the longest time, while the rest of us argued the world and whether we truly needed it. Then of a sudden, Bill would lob a bombshell comment into the debate, altering the shape of the rest of Thanksmas, throwing everybody else's yammerings into a cocked hat. Then our resident info-lobber would sit back in silence and enjoy the ensuing fireworks. At the last Thanksmas he attended, one year ago, I finally stumped Bill. I made him watch an old episode of the sitcom Three's Company—I was somewhat surprised to discover he was already a fan—in which a pompous, Brobdingnagian food critic is invited to dine at the characters' apartment. With much relish, I expounded upon the obvious "separated at birth" coincidence between Bill and "Jason Dafarge," played by Jay Garner. At last, I had lobbed the bombshell! Bill loved the episode, laughing and even seeming a bit embarrassed. I called him Jason a couple of times, but he just emitted one of his patented, exaggerated sighs. I regret I never had the chance to write a review of the Heinlein biography. How I longed to eviscerate, defenestrate, and armageddonate that book, no matter how brilliant the damn thing was! RIP, Bill; not surprisingly, you leave a mighty big hole. Nota beneMy wife and sundry friends contributed mightily to this tribute. If any part offended you, blame one of them. Additional remembrance from Lee Porter, yet another "friend of Bill"I don't remember how it came up, but for some reason I mentioned the Poeme Electronique by Edgard Varese, which is not exactly top 40 material these days. Patterson did not miss a beat and replied, "I haven't heard that in ages!" *Personal GPS’s didn't exist back then, but we didn't need one: Bill had an intimate and encylopaedic knowledge of every pastry parlor, sweetshop, and cakery in San Francisco, including exotic tooth-decayers of Chinese, Japanese, Javanese, Crimean, Ethiopian, and extraterrestrial origin. Had Bill been teleported to the backwoods of Barsoom, within eight minutes, he would have located the nearest sushi bar. | ||||||||||||||||