Looking Back at the Sunset

by William Alan Ritch

Robert A. Heinlein—In Dialogue with His Century:

Volume 2: The Man who Learned Better

By William H. Patterson, Jr.

When I was a kid in elementary school, the first novel I ever read was Have Space Suit—Will Travel by Heinlein. Sure, I also read about Miss Pickerell and Danny Dunn and Lucky Starr. I followed the adventures of Space Cat and Freddy the Pig. I solved cases and had adventures with Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys and Rick Brandt. I explored London with Poppins, Middle-Earth with Bilbo, the Mushroom Planet with Mr. Bass and Oz with Dorothy—but there was NOTHING in my elementary school library like a book with the markings “F - HEI” on the spine—nothing like a book by Heinlein.

First Edition Cover

First Edition Cover

Starting with Rocket Ship Galileo, from 1947 to 1959 Heinlein wrote a baker’s dozen of science fiction novels targeted at boys, for Scribners. Later this category of book would be inaccurately termed “Young Adult” or “YA”—but back in the 1950s they were called “juvies.” Heinlein’s juvies were the best.

Heinlein’s juvies were revolutionary—and subversive. They are some of the most subversive books I have ever read. He did not talk down to his audience—he treated them like grown-ups and expected them to be smart and inquisitive. He mixed action and adventure with believable characters, realism and naturalistic dialog. He subtly revealed character with seemingly simple writing.

After I became an adult and re-read all of the juvies, for the first time I wondered—how did he ever get these books published? The answer is—he almost didn’t.

Heinlein wanted to tell a story of young engineers engaged in an exciting and technically challenging project. And what could be more exciting than going to the moon? Thus Rocket Ship Galileo is the story of three teenage rocket geeks teaming up with a real rocket scientist to build a nuclear-powered rocket to the moon. In addition to the technical problems they must face and solve, there is adventure when the boys discover a secret base of Nazis who have holed-up on the moon.

Heinlein created a trope in 1947 that survives to this day—see the movie Iron Sky. Borrowing a little from the original Tom Swift, he enhanced the trope of invention adventure.

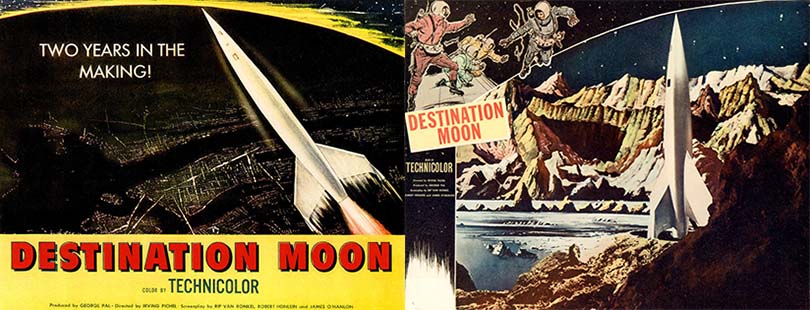

The book was the basis of Heinlein’s first movie, Destination Moon (directed by George Pal). Heinlein worked furiously to make this movie right and his efforts are visible on the screen. Unfortunately, it takes a lot of time for a writer to have any influence on a movie, so Heinlein had to spend his time not writing stories, but instead fighting the idiots who thought they knew better. The process did not stop Heinlein from continuing to work on movies and TV series, but it made him a lot more cynical about the process.

Rocket Ship Galileo is a good story but it had only the faintest glimmer of the kind of story Heinlein would tell in his future juvies.

The real purpose of these novels was to provide a pattern of how to become an adult—how to grow up. Heinlein was developing complex themes that hid in the seemingly simple plots of these novels. With the second book, Space Cadet, Heinlein introduces a theme that is one of the cores of his personal philosophy: the difference between a Civilian and a Citizen, a person who chooses to defend the civilians even at the risk of his own life. There is even a subtle examination of racist attitudes. Subtle because it ignores intra-human racism and instead looks at the human treatment of the intelligent, but “primitive,” inhabitants of Venus.

This point is amplified in Heinlein’s next juvie, Red Planet. This time it’s the Martians that are assumed to be pets. They are really the nymph form of a very old and sentient species. The antagonists want to take the hero’s “pet” and ship it to the London Zoo on Earth. Our hero resists. Conflict ensues. The hero learns to defy authority (the school’s headmaster and some cronies in the Terran colonial government) for the sake of an individual. I cannot begin to tell you how wonderfully subversive this tale is for a young person. The idea that adults can be wrong! Wrong and wicked. Heady stuff.

First Edition Cover

First Edition Cover

Not surprisingly, Heinlein also butted heads with his editor, Alice Dahlgliesh, because of this book. She was offended by the young students carrying handguns and rifles. She wanted that aspect toned down, never mind the clear parallel with young people on the American frontier. I am sure the reader will also be unsurprised that the gun-toting was also excised from the TV movie adaptation of the book made 45 years later.

Dahlgliesh also objected to a scene in the novel where our hero, Jim, and his Martian friend Willis, are horsing around on Jim’s bed, and soon after Willis lays its eggs on the same bed. Horrors! Too risqué for children. Were Burroughs’ Barsoom books banned because Dejah Thoris’ egg-laying? Had no children ever grown up on a farm with chickens? Throughout the writer/editor relationship it was Dahlgliesh who reined in Heinlein’s open-mindedness and individualism. She always said she was trying to foresee the complaints from the libraries and bookstores but I think that Heinlein used her as the mental image he had for the Miss Grundys of the world trying to stamp out fun and in Heinlein’s words, “make the world safe for morons.”

In his next juvie, Farmer in the Sky, Heinlein succeeding in building a book that was both for adolescents and that would complete against the adult science fiction books of 1950. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Astounding praised its mature nature and attention to detail. Years later, Jack Williamson pointed out its “harsh realism.”

With Between Planets, Dahlgliesh was again complaining. This time it was about the boy-meets-girl subplot. Even though these books were supposed to be targeted at boys Heinlein had noticed a lot of fan mail came from girls. Dahlgliesh also was wary of the revolutionary politics that Heinlein built into the plot. Once again the young hero sees first-hand the cruelty of authority trying to keep a colonial power under its control. Heinlein’s juvies celebrate the American mythos of opposing tyranny and celebrating individualism. Reading these ideas today they seem even more radical than they did in the 1950s. This book promotes the concept of paying a debt “forward” instead of “back”—a concept that was fundamental in Heinlein’s later fiction and his real life.

1952’s The Rolling Stones was a fun romp through the solar system—it was also a carefully researched story and a detailed illustration of economics and the laws of supply and demand. It introduced characters, such as Hazel Stone, that Heinlein would use again in later books (The Moon is a Harsh Mistress). One of the cleverest ideas in the book is the flat cats, which were “born pregnant” and reproduced like crazy when freed from their ecological niche, filled with their predators. Heinlein acknowledged that he lifted some of this from Ellis Parker Butler’s story, “Pigs is Pigs.” And later David Gerrold lifted the idea from Heinlein and turned them into tribbles on a famous episode of Star Trek.

Once again, Alice Dahlgliesh complained about the unsavory sex habits of the flat cats—complained to “protect” Heinlein from the backlash of the library buyers. These annual and predictable dust-ups with Dahlgliesh had begun to sour Heinlein on writing books for kids. The trouble was becoming more than it was worth.

With Starman Jones, Heinlein moves the political more directly into the characters lives. Heinlein takes direct aim at labor guilds (hyper-unions) and closed shops. It celebrates yeomen individualists. It deals with moral ambiguities in its main characters and does not resolve them. In other words, it is an exposure to the world of the adults at an emotional level—not just the intellectual one. That’s what Heinlein did that no other writer of juvie SF novels could. He wrapped his hands around the emotional strings of the young person and pulled him into adulthood.

First Edition Cover

First Edition Cover

Less political is Heinlein’s next book for Scribner’s, The Star Beast. Nevertheless, Heinlein could not escape controversy. One of the under-aged characters has divorced her parents and Dahlgliesh objected to that (despite the fact that this represented contemporary American law!). Later a reviewer for The Library Journal, with the Dickensian name of Learned Bulman, wrote to Scribner’s also complaining about the child-divorce and asking it be removed in the second edition. Dahlgliesh told him the writer insisted that it be left in. Dahlgliesh forwarded the discussion to Heinlein who, rather than sympathizing with her editorial position rightly attacked her for her cowardice. The relationship continued to deteriorate.

Also of interest: the ruler of Earth is a Mr. Kiku—a black man from Africa in an arranged marriage. Different cultures. This book also continues Heinlein’s conceit of aliens standing in for human racism. There is quite a kerfuffle in the book about which character is the “pet” and which is the “owner.” It’s played for humor, but an intelligent young reader is made to questions his viewpoint about such things.

His 1955 novel, Tunnel in the Sky, is the harshest and most adult of his Scribner-published juvies. It is about the survival of students on an alien planet. It is supposed to be a test of a few days’ survival but a snafu makes their stay indefinite. The planet is a harsh environment with no room for mistakes.

Heinlein decided to make a more direct and a more subtle racial statement in this book. The hero, Rod Walker is black. It is not stated directly—but implied by context and description. Also, a telling point, is that his classmates expect him to wind up with a girl named Caroline, who is directly described as black. Instead he winds up with a different girl, “Jack” (Jacqueline Daudet) whom he first takes to be a boy!

In some ways it is an answer to Golding’s Lord of the Flies but all indications are that Heinlein had not heard of Flies when he was writing Tunnel. Both novels posit a group of young people separated from adult supervision by a transportation accident. In Golding’s book a dangerous fascist dictatorship emerges. In Heinlein’s, the fight for survival unites most of the young people to that common goal.

There are many differences between the books: for one, Heinlein’s students are older and more of an age. But I think that the real difference is that Golding is British and Heinlein American. Golding sees the lack of civilization as a lack of the proper order of lords and commoners. Heinlein’s American viewpoint is that the alien planet is a wilderness that must be conquered and held by the civilization of man. Even though there are good and bad humans in Heinlein’s book, their common enemy is nature. Golding sees the real foe as man.

Despite problems with his publisher, Heinlein wrote to Dahlgliesh of this book: “my stuff for kids is the most important work that I do… I hope to keep it up for a long time.”

Time for the Stars has long lingered in my head. I first read it in the early 1960s. Not for its political points—but for its mind-warping science. It dramatized the nature of relativistic time-dilation and the twin paradox. Our heroes are twins—twins who share a telepathic link. With some hand-waving the idea is that telepathy is instantaneous and not affected by distance. So one twin, Tom, is sent out with a group of interstellar explorers on a ship with constant acceleration—getting closer and closer to the speed of light. Back on Earth the other twin, Pat, stays. The twin traveling at near light-speed ages slower than twin on Earth. As the exploration continues the Earth-bound Pat gets older. Fortunately, his offspring can continue the telepathy. As the novel draws to a close our Tom has been “talking” with Pat’s great-grand daughter since her childhood. His brother is long dead. Earth invents faster-than-light travel (because of the telepathy research) and picks up Tom’s crew on their “slow” spaceship. Tom comes back to Earth and marries his own great-grand-niece. This non-controversial incest presages the subject that Heinlein will deal with more explicitly in later books.

First Edition Cover

First Edition Cover

In Citizen of the Galaxy Heinlein brings to the forefront one of the philosophical points that most concerns him: what is the nature of citizenship and responsibility in a civilization? Our hero, Thorby, starts off a slave. He is bought and educated and eventually transfered upon the death of his “owner.” Along the way he learns about family, friendship and eventually citizenship. Some of this was written in response to the Hungarian revolt of 1956 and some of it is based on Kipling’s Kim (Kipling was a favorite writer of Heinlein), but the spine of this book is pure Heinlein. When it was serialized in Astounding John W. Campbell wanted to call it “The Slave” since it dealt with various definitions of slavery. Heinlein was insistent that citizenship was his true point and the slavery was there for the contrast. “All creatures everywhere are constrained by the circumstances but the mature creature (that is to say, a “citizen”) faces up to the constraints in a mature fashion.” Campbell gave in.

There was a lot for Dahlgliesh to object to in this book. For instance, some throwaway lines about “girlie magazines” and “pin-up pictures.” But she also objected to the characters disrespect of the state religion. A made-up religion that upheld slavery and gladiatorial combat. But, to the watchful dragons of children’s books, any disrespect of religion was not to be tolerated.

Have Space Suit—Will Travel (1958) is dear to my heart. Unlike the other juvies written before and after, this is more a story about kids. The protagonists are younger and the story-telling simpler. Nevertheless this is a powerful book about the nature of humanity and its place in the universe. We meet an intergalactic tribunal that judges other races, like Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still. If the race under study is judged too dangerous it is exterminated. Dahlgliesh objected—not to this genocide—but to our hero’s action of stomping on the skull of his enemy. Heinlein balked. He said, “our present peril [with the Soviet Union] has been brought on by large measure by weak-stomached ladies of both sexes, tender-minded creatures who fear fighting more than they fear slavery.” He did not change a word.

And another thing!

Why was Heinlein subtle in his assignment of races to his juvie characters?

Was it to force me to listen to a smug English major graduate student deliver a paper that attempted to prove that no matter how open-minded and ahead of his time we thought Heinlein was, he was just another sexist, racist, white guy who NEVER used a “person of color” as a protagonist in his stories? Despite the explicit statement that Johnny Rico of Starship Troopers was Filipino. Despite the intentional portrayal of Eunice in I Will Fear No Evil as of indeterminate race. Despite the hero of The Moon is a Harsh Mistress being named Manuel Garcia O'Kelly-Davis and as pureed a race as the moon could provide. And despite the subtle indications of Rod Walker’s race in Tunnel in the Sky. All obviously too subtle for an English major since she was surprised by these revelations despite having allegedly read each of the books “many times.” Was it?

Or was it because his editor, Alice Dahlgliesh, fought to expunge the details of such references because she feared it would cost them sales in the Deep South? And was that an actual fact of sales to southern libraries or a prejudice of a New York editor toward the “benighted South?”

And what about Farnham’s Freehold? More on that, later.

His last juvie for Scribner’s was 1959’s Starship Troopers. When he presented it to Alice Dahlgliesh she rejected it outright as too philosophical and too argumentative—read: too adult. He submitted it to Doubleday and to Campbell (for Astounding)—but they found it too juvenile. Here was a book that was between worlds.

First Edition Cover

First Edition Cover

Fortunately G. P. Putnam’s wanted the book and didn’t call it a juvie or an adult book. It was simply a new novel by Robert A. Heinlein.

Heinlein’s time with Scribner’s was now behind him and a new phase in his career as a novelist was beginning.

As we move toward the 1960s his books become more complex and more adult. They are now about young adults instead of little kids. We will see another juvie in 1963—with a girl as the point-of-view character. Even though Podkayne is the book’s title character and (mostly) it is her point-of-view, this is another subtle sleight-of-hand. The real subject of the book is Poddy’s little brother: Clark—the genius.

Destination Moon was a film that Heinlein had wanted to make for a long time. He promoted the cause of space exploration in stories and articles for the mainstream magazines. A fiction movie, not a documentary, could be his most persuasive venue yet. Back in Volume 1, Patterson tells of his attempts to get a realistic trip-to-the-moon movie made with Fritz Lang. After all, Lang had directed such a movie back in 1929: the silent classic Frau im Mond, which was thrilling, technically accurate and visually impressive. Think what could be done in the late 1940s.

The deal with Lang fell through—mostly for monetary reasons, but he soon began working with writer “Rip” van Ronkel to develop Rocket Ship Galileo into a movie. They worked well together.

Although the book Rocket Ship Galileo and the movie Destination Moon both tell the story of man’s first rocket to the Moon, the latter is “loosely based” on the former. They are really two distinct works. In fact, Destination Moon has more in common with “The Man Who Sold the Moon,” which Heinlein wrote while he was developing the movie.

Destination Moon was, in Heinlein’s eyes, a story about man’s love of his destiny: to inherit the stars. In practice it taught him about the crazy development hell of Hollywood.

The project got attached to George Pal, who was just about to launch the first great science fiction film career in the history of Hollywood.

Since Pal could not get a major studio to back this film he had to go independent—which limited the money coming it. Still, given the smaller budget, the film became visually impressive. The spectacular Technicolor photography made it look like an actual event. Chesley Bonestell’s background paintings of the Moon were photographic. Pal was smart enough to make Heinlein the technical adviser, giving him more power than a screenwriter.

The quantity of money to create a product in Hollywood is like the amount of fuel it takes to send a rocket from the Earth to the Moon. Copious amounts are required and it is hard to get—except when it does come in. Then there is so much that someone is likely to get burned. Various Hollywood people would try to “improve” the film. To quote Heinlein: “I find that when an unscientifically-trained buyer wants to rewrite science fiction, there is almost no way to satisfy him.”

Nevertheless the big budget (for an independent film) and excellent hype from the publicity department made Destination Moon a highly-anticipated film. It spurred even lower-budgeted films to be made. The “first to be second” film, Rocketship X-M, actually beat Destination Moon into the theatres by a month. It was shot in 18 days, used Mars as the setting (with the red-tinted California desert standing in), and military surplus for costumes and props. Destination Moon had big-budget technical delays.

Patterson points out that it was “Destination Moon that kicked off what was virtually a craze for space movies.” What started with 1950’s Destination Moon led directly to 1968’s 2001: a space odyssey—and culminated in 1969’s actual trip to the Moon as seen on television and produced by NASA and the American people.

So—what is actually juicy in Patterson’s biography? We learn of one of Heinlein’s best kept secrets. He was very generous to his fellow writers.

His generosity to his philosophical fellow travelers like Jerry Pournelle and Larry Niven should come as no surprise. We learn of a time when Jerry Pournelle had to spend an unexpected overnighter at the Heinlein house—and this act of hospitality had to remain unreported, at Heinlein’s own request, until after Heinlein’s death. Also revealed are the surprising friendships and generosities to non-Heinleinean writers like Theodore Sturgeon and Philip K. Dick—writers with very different styles and focuses.

He helped writers be writers. He gave Niven and Pournelle (who had been published writers for several years before writing together) so many notes on the manuscript for their first joint novel that they had to rewrite the book. It became one of the best things they have ever written, together or separately: The Mote in God’s Eye. Sturgeon was once suffering from writer’s block and asked Heinlein for a few ideas. He sent Sturgeon the story ideas (about 10) as well as some money and a pep talk in the letter.

A more personal example: I have known Brad Linaweaver since college. I encouraged him to read more Heinlein and he became a Heinlein fan. (He, likewise, encouraged me into being more a fan of Bradbury’s). It meant a lot to me that Patterson ran the following quote from a letter Heinlein wrote to Brad after reading his novella, "Moon of Ice," in Amazing: "It's a good story and I hope you win the Nebula with it." This started Brad down the road to his first novel.

He gave a young writer/journalist/fan one of the longest, most detailed, and most personal interviews of Heinlein’s life. What was it about J. Neil Schulman that got Heinlein to open up so much, when he was usually so reserved during interviews? Maybe he recognized another budding science fiction writer and was “paying it forward” as he so often did.

Patterson has also rewarded Heinlein fans with facts that we have had to assume for many years. Until the publication of these volumes his defenders had to make educated assumptions about what Heinlein really meant in his books. There was little to point at in Heinlein’s words ex libris. And we have all had to listen to droning pendants reminding us that we cannot tell what a writer really believes based on what his characters say.

True. But now we know. Patterson has given us a treasure trove to prove or disprove those assumptions. Now we can talk authoritatively about Heinlein’s philosophy, what he was trying to accomplish outside of his life and what his books really said.

|