Looking Back at the Sunset

by William Alan Ritch

Robert A. Heinlein—In Dialogue with His Century:

Volume 2: The Man who Learned Better

By William H. Patterson, Jr.

In the previous volume of this biography we followed Heinlein’s writing career from his early success in publishing stories in the top-paying SF magazine at the time, John W. Campbell’s Astounding. We also saw how World War II interrupted most of Heinlein’s writing because of the war effort. His health made him unfit for service, but he could still work stateside as a civilian for the government.

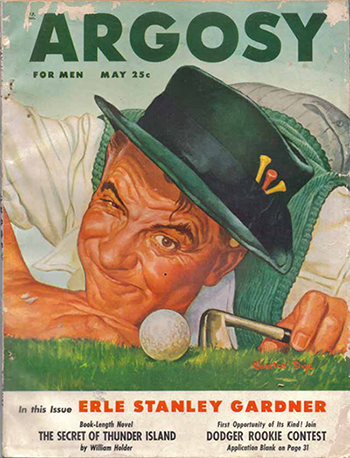

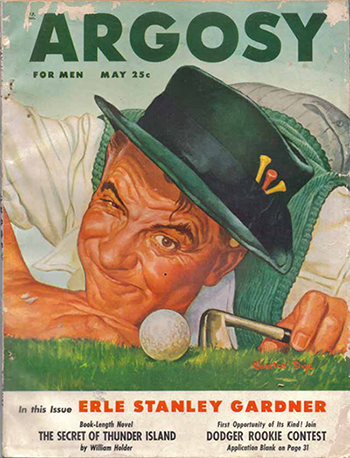

The May 1948 Argosy featuring

The May 1948 Argosy featuring

Heinlein's "Gentlemen, Be Seated!"

After WWII Heinlein was determined to break out of the low-paying SF magazine ghetto. This was a ghetto that nurtured SF and SF fans. The more people that read these kinds of stories the more money Heinlein could make writing them. Heinlein was a professional writer, after all.

And one could not be truly successful just publishing stories in the pulp magazines (even Astounding)—unless one could create stories at an almost inhuman rate. There were some fine writers who could accomplish that. Heinlein was not one of them. Besides, he had more literary aspirations.

There were two realistic options—and a long shot: sell short stories for the “slick” magazines, sell novels to book publishers—and the long shot: sell to the movies. Heinlein accomplished all three—although his success with the long shot was very limited.

After the War, Heinlein was the first of the pulp SF writers to crack the slicks. He was able to sell short stories to The Saturday Evening Post, Argosy and Blue Book. Other genre writers would follow—including a young fan of Heinlein’s named Ray Bradbury as well as another science fiction writer who started in Galaxy, moved to Playboy and would go on to win the Pultizer Prize, Michael Shaara.

Money was not the only reason that Heinlein wanted to sell to the bigger magazines. He had something to say to a larger audience. He wanted them to understand the importance of science and engineering. The atom bomb was the ultimate proof that technological superiority is what wins wars, and Heinlein wanted to educate the population about space exploration and scientific research.

And the money was good.

But the money was better from published books. Surprisingly Heinlein’s first published novel, Rocket Ship Galileo accomplished several of his goals simultaneously. He was now a published novelist. The book educates and excites its readers about the imminent fact of space travel—especially readers who are still young and might choose a career in the field. And it lead Heinlein into working on the adaptation of the book into a movie.

|